Water Works artist Inkpa Mani resigned amid charges of cultural appropriation

A prestigious public art project meant for a downtown Minneapolis park is in limbo after the artist chosen for the job resigned amid accusations of cultural appropriation.

The situation echoes many instances of Native-presenting people called out to prove their identities across Indian Country, raising questions about belonging — who is permitted to practice Native arts and who gets to decide.

Inkpa Mani, a 25-year-old Dakota-speaking artist who lives in Wheaton, Minn., was selected in March by an independent panel of community members to create a stone sculpture overlooking St. Anthony Falls. Opened in 2021, the Water Works park area is sacred to the Dakota, who call it Owámniyomni.

Mani submitted concept designs for a series of approximately 40-feet-tall, forked pillars made of black granite and limestone. The “Y” shape references Bdote, the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers, he said.

But in July, the artist resigned. The city has not widely announced his departure nor what it means for the Water Works art project.

The Documenters, a citizen journalism outlet, first reported that the Mnisota Native Artists Alliance and Minnesota Indigenous Business Alliance had complained about the project.

The crux of their opposition to Mani: Though he was adopted by a Dakota family, he is not Dakota by blood.

According to a joint statement by the organizations, many Native artists expressed concerns about Mani’s validity and the “lack of authentic Dakota representation” in the project, but they were ignored by the city.

“We are unapologetically saying that Native artists have the sovereign right to uncover and stop cultural appropriation in their communities,” the organizations said.

‘Facts were not provided’

The city’s original call for artists emphasized applicants for its $400,000 commission should have “in-depth knowledge and understanding of Indigenous history, culture and language … and experience celebrating Native American culture.”

It stopped short of reserving the opportunity for a particular ethnicity. But some of those involved in the selection process said a Dakota artist deserved the job and that they were misled to choose Mani.

“I was led to believe through his name, his application materials, that Inkpa Mani was not only Native, but Dakota,” Mona Smith, a selection committee member, said in a statement. “The facts were not provided to us. And the days we live in require complicated honesty, transparency.”

Ginger Porcella, executive director of Franconia Sculpture Park near Shafer, Minn., added her impact statement to the complaint.

“I wanted to stand with these artists that had been hurt by [Mani],” she said. “It was really hard to hear how his lies had further traumatized artists who have already been traumatized.”

In his Water Works application, Mani said his family comes from “all the Dakota and Lakota bands of the Great Sioux Nation.”

“I have sat with my elders and taken the time to listen and remember our history,” he wrote. “I am a cultural practitioner and contemporary artist working with Dakota communities.”

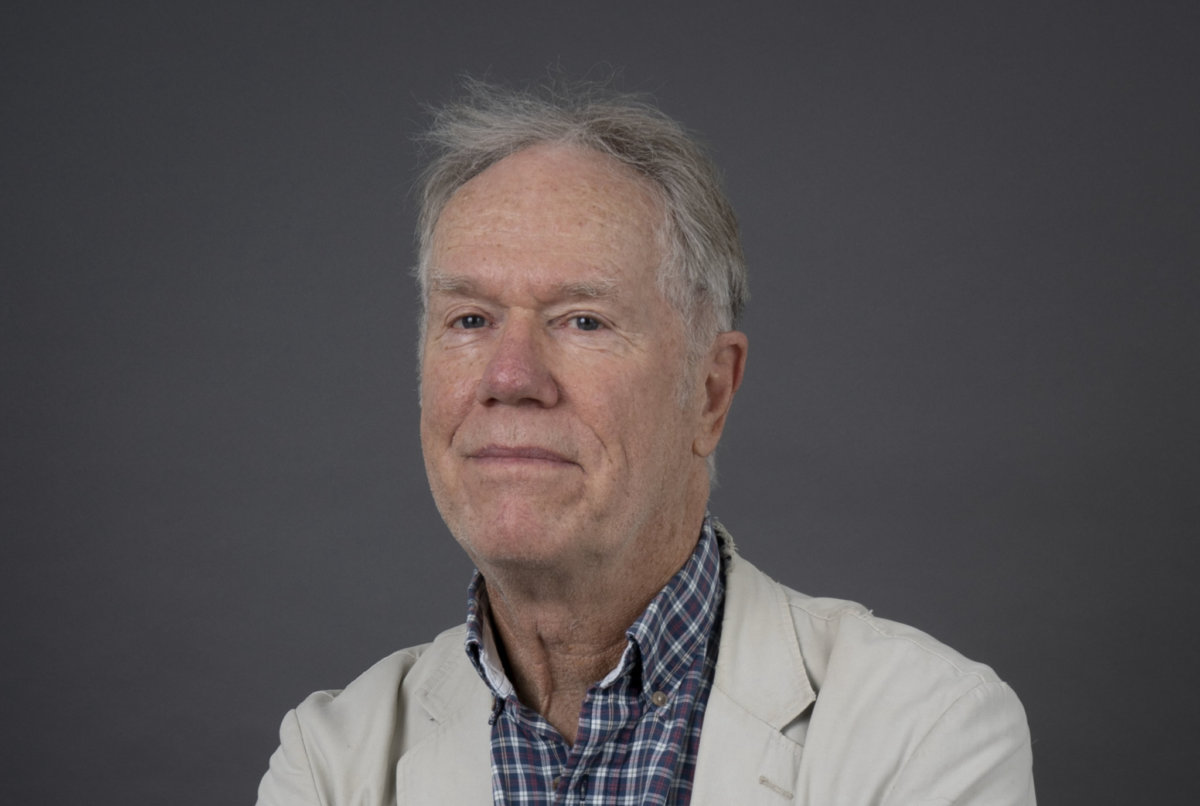

Speaking with the Star Tribune, the artist clarified he was born Javier Lara-Ruiz to a Mexican-American mother. She married a Dakota man, whom he called “dad,” when he was a child. After they divorced, he was adopted by Sisseton Wahpeton tribal members and embedded into Dakota culture. His partner and daughter are Dakota.

“When I talk about my work, it’s really reliant on my experiences and how people have brought me into their circles and into their families, but no, I am not Dakota,” Mani said.

He said he resigned from the Water Works project for reasons including his mother’s death in January, the long commute to Minneapolis and his teaching job at Tiospa Zina Tribal School on the Lake Traverse Reservation in northeastern South Dakota.

“Thinking about the city … and the different communities involved, I don’t want to be an obstacle for anything,” he said.

‘He’s family’

The organizations that submitted complaints about Mani demanded the city rescind his contract and issue a public statement recognizing Native artists’ “sovereignty over the management of their arts and culture.”

They also requested that city attorneys attend training on the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, a federal law restricting the right to market Native American-made products to tribal members or other individuals tribe-certified as Indian artisans.

A July 8 city statement sent to dozens of individuals and organizations involved in the project apologized for “the pain this experience has caused within the community.”

Minneapolis spokeswoman Sarah McKenzie said city staff encouraged the community members to meet directly with Inkpa Mani, but they declined.

The artist’s resignation did not sit well with selection panelist and Dakota historian Syd Beane, who said he still believes Mani had more knowledge of Dakota language and culture than other applicants.

Traditionally, people who were adopted or married into tribes, joined the ceremonies and practiced the values became a part of that community, he said.

“That’s more what it seems to me Inkpa Mani has done,” said Beane. “Increasingly, these identity issues, they’re forcing people to get back and study the history of their families, and that’s a good thing. … But I think we have to be very careful when making a decision about somebody else’s identity.”

Beane said Mani will have to be clear about not being an enrolled tribal member in the future.

Mani’s adoptive family in South Dakota is frustrated that the complaining organizations did not seek their point of view.

Patricia Gill-Eagle, who co-founded Tiospa Zina Tribal School, calls Mani her grandson. As a child, she sat him by the fire and taught him the stories of their people. It was her family that adopted him and gave him his Indian name in a ceremony.

“He Sun Dances with us. He knows everything we know,” said Gill-Eagle. “Whoever is talking about him, they don’t know him and they don’t know us.”

This summer, Mani joined a Sisseton Wahpeton delegation of horse riders who rode to White Earth Nation‘s Treaty Days powwow, retracing a historic meeting between the tribes for the first time in more than 50 years.

“Of course, Inkpa was a part of that because he’s family,” said LeeAnn Eastman, a Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate member who calls Mani a brother.

She said if the Minnesota complainants had allowed the family to take time off their jobs and travel the four hours from the reservation to Minneapolis to stand up for Mani, they would have.

“Traditionally, our ‘hunka’ adoption relationships were even stronger than blood,” said Tamara St. John, tribal historian and South Dakota legislator. “My key objections to this attack on him are … that they extend so far as to not respect him as an Indigenous person, and seek to separate him from the whole cultural upbringing that he has been exposed to and received from elders.”

After Mani resigned Water Works , a cousin of his step-father involved with the complaints in Minnesota made the same complaint in Sisseton to stop another of his stone sculptures — that of a Dakota woman — under development there, St. John said.

She arranged a community meeting on Aug. 17. The complainant did not appear, but Mani’s friends and family did. Women of the Buffalo Heart Society, who work in tribal preservation, endorsed the sculpture by offering prayers with tobacco.

The person who made the complaint did not respond to a request for comment.

‘A wake-up call’

Dakota artist Marlena Myles, who advised the city on the Water Works project, said she felt deceived by Mani. She reached out to him directly and urged him to clarify his ancestry.

“I wish he would stop letting people assume he is Dakota,” Myles said.

Over the years, Mani has been imprecise about his identity.

In a 2017 video interview, he said he was “adopted into the Dakota and Sioux way of life.” In a 2021 podcast, he said, “I’m Dakota.”

Lakota artist Keith BraveHeart attended the University of South Dakota with Mani. He advised the younger artist about navigating the Native arts world, particularly when progressing to projects involving large sums of money.

BraveHeart sees an opportunity for discussion across Indian Country about what it means to make and share Native art. He said he respects the artists involved in the Minnesota complaints but questions whether they could have worked with Mani to sort things out.

“When we see certain kinds of incidents that occur where it starts to revert to this materialistic game, or becomes muddy … it becomes ultimately unproductive,” said BraveHeart. “There should be more of a patience involved here. There should be understanding that comes from all of this.”

With issues of Native identity, changing tribal eligibility and ancient adoption traditions are all churning within Indian Country, said Robert Lilligren of the Native American Community Development Institute in Minneapolis.

In 2019, Red Lake Nation passed a major expansion of membership by moving away from blood quantum, a federally imposed requirement that enrollees have at minimum 25{5b4d37f3b561c14bd186647c61229400cd4722d6fb37730c64ddff077a6b66c6} tribal blood.

And this summer, members of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe voted to eliminate their blood quantum requirement, which had excluded the children of many tribal members from full citizenship.

“The movement has been toward permissiveness and broadening the definition,” said Lilligren. “I think this was a wake up call for the community that we need to formalize this conversation.”