Sean Kirst: An old high school teammate honors Bob Lanier, ‘in neighborhood fashion’ | Local News

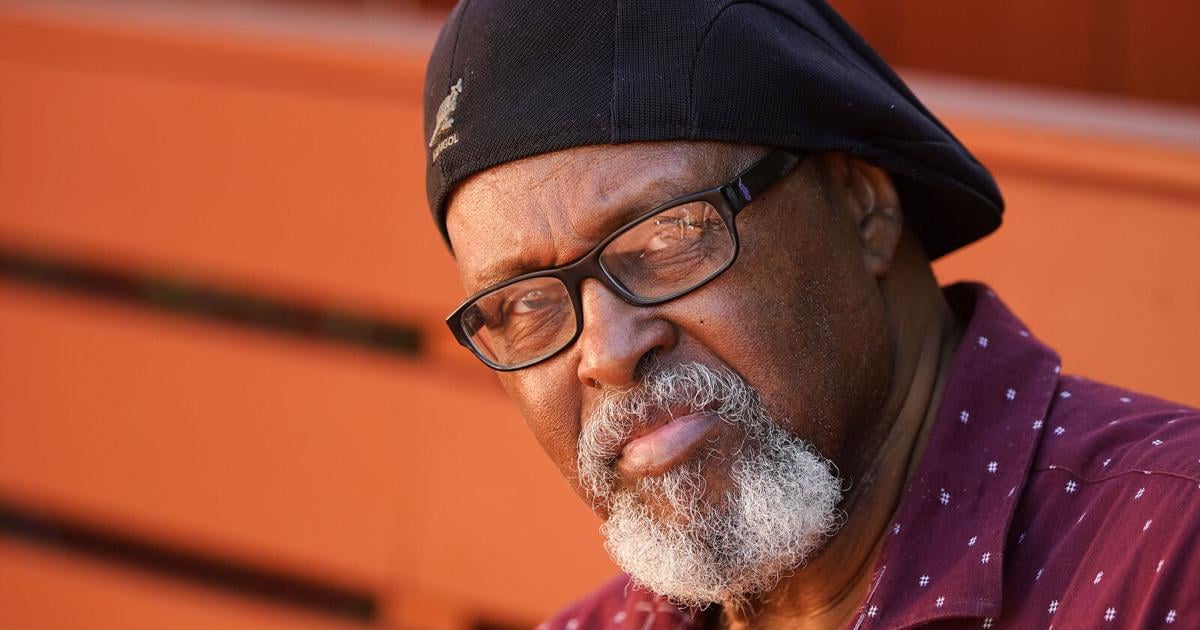

Gregory Brown could have easily turned down the call about Bob Lanier. It has been only five weeks since the death of Brown’s wife, Yvonne, and he offers a description of love at first sight, in remembering her, that he draws from some favorite lines in Mario Puzo’s “The Godfather.”

She was a thunderbolt in his life, beginning in the instant he saw her in a Black dance workshop at the University at Buffalo, more than 50 years ago.

Yet losing Yvonne, and a promise made in her memory, has something to do with why Brown picked up the phone. Not long ago, he was in line at a Porter Avenue ice cream place when he started talking to the guy next to him, who happened to be a young college basketball coach. Brown told him, “Yeah, in high school, I played with Bob Lanier.”

The coach, roughly a half-century younger than Brown, was puzzled. Who was that?

A senior photo of Bennett High School basketball star Bob Lanier from the 1966 yearbook, courtesy of Greg Brown, a teammate.

“I used to brag about being a teammate of Bob’s,” Brown said, “and I had no idea the time to do that bragging was coming to an end.”

People are also reading…

To Brown, aware that too many of his high school teammates are gone, the encounter said everything about community memory – and why it takes on even greater importance after Lanier’s death at 73, a few days ago.

“The sun sets on all us eventually,” Brown said, meaning you need to share the stories.

At Bennett High School, he was a year behind Lanier, a soon-to-be legend who – after nearby Canisius turned him down – would propel St. Bonaventure to the greatest basketball season in its history, a guy many swear was one heartbreaking NCAA tournament knee injury away from bringing a national championship back to Olean.

Lanier went on to be a great center in the National Basketball Association. He was president of the players’ association and then a coach, a worldwide league ambassador and a monumental administrative figure in the ascendancy of the modern NBA, but Brown did this interview based on an understanding:

When he thinks of Lanier, he goes back to the place where they grew up.

A photo of the Bennett High School boys basketball team from the 1966 yearbook. Bob Lanier is seated in the front row, holding the trophy. Number 11, to the right, is teammate Greg Brown.

“We all came of age at the Masten Boys Club,” said Brown, whose older brother Al – gone now for 11 years – was a fierce power forward who played alongside Lanier at Bennett before they graduated together 56 years ago this spring.

Part of the neighborhood tale is well-known: Lanier – stunned by being cut from the team as a sophomore – brought all that hurt to Lorrie Alexander, a Boys Club mainstay and mentor who helped an upset high school kid raise his game to a triumphant level.

A private, giving nature is one of the many qualities that local basketball dignitaries remembered about Lanier, a Buffalo native and a Bennett High School graduate who died Tuesday in Arizona. He was 73.

Brown’s recollections sweep through the community. They intertwine with why a note about Lanier’s passing has already generated more than 300 comments on “Buffalo: A Toast to the Town” – a fast-growing Facebook memory page that Bartel Miller began with a shared emphasis on memories of women and men raised in Buffalo’s historically Black neighborhoods, a page that quickly grew to wrap in the whole community.

Miller heard from people who played dodgeball with the hard-throwing Lanier in junior high, or remembered when the teenage Lanier stopped by to help move furniture. One correspondent, Molly Majer, recalled how the young Lanier would sometimes give her delighted great-aunt, Helen Bless, a ride home from a Your Host restaurant that was her favorite stop.

“He knew where he came from,” said Miller, echoing Lum Smith in marveling at an extraordinary era for basketball in Western New York: Smith, a longtime Buffalo educator and community historian, remembers evening basketball workouts with some friends at Buffalo State during a period when a new-to-the-NBA Lanier and the great Randy Smith would show up to run the court.

Brown’s earliest memories of Lanier involve a backdrop of the newly built Kensington Expressway. Construction of that sunken expressway complicated daily patterns for Buffalo kids who had once casually moved from block to block in Cold Spring and nearby neighborhoods, Brown said. Lanier was at School 74, while Brown and his brother Al were at School 54, and they came to know each other while battling on the court in such places as Trinidad Park.

Newspaper accounts of Bennett’s 1966 victory over Emerson for the Buffalo Board of Education boys basketball championship.

“That’s where the hoop was, where so many of us learned the game,” Brown said.

When Lanier showed up, it was as a leader of guys who came to play from Northland Avenue. Neighborhood showdowns built into an intense eighth grade rivalry that Brown said ended with School 54 winning a city title, just before these former adversaries all ended up on the same side at Bennett.

As upperclassmen, they meshed into a power in what the kids called “The Nickel,” short for Nickel City. The culmination for the Tigers was a 66-55 victory over Emerson in March 1966 for a second straight citywide Board of Education title for new Coach Fred Szwebjka, as laid out in old clippings provided by historian Brian Frank of the Herd Chronicles.

Lanier’s touch would have made him great in any era. He had a better bank shot, with the hook or on mid-range shots, than any big man today.

“Me? I rode the pine,” Brown said of his junior year. But he remembers how Lanier had 25 points against Emerson, despite foul trouble and a defense geared to stop him, while three others scored in double figures for Bennett: Brown’s brother Al had 15 by “pouring rain with corner jump shots,” the late and gifted Kenny Maclin added 12 and point guard Joe Green laid in 10.

These were great rivalries, forged by guys who honed their skills in relentless summer games at Delaware Park. Brown said crowds gathered to watch Lanier and other playground stalwarts go up and down, players that often included future mayor Tony Masiello.

“There wasn’t a lot of money to go around in those days,” said Brown, 72, a retired lawyer whose dad worked at a plant that supplied coke for steel production. A lot of teenage socializing was done on the playgrounds or around the Masten gym, and when Brown thinks of it now, it occurs to him:

In some ways, they were rich.

From Bennett, Brown went on to Brown University, a great Buffalo story in itself: The son of a couple who came here from Louisiana during the Great Migration made his way to an Ivy League school, honoring parents who never had that chance. Lanier, at the time, was burning it up for Bonaventure, and Brown used to tell his classmates, “Yeah, I know that guy.”

At one point, his college friends put him to the test. Lanier was playing against Fairfield University, not far away, and they said, “Why don’t we go so you can say hello to your buddy?” Brown said sure, but he had no idea how Lanier would react to a childhood friend who had been a benchwarmer on their high school team.

Bob Lanier goes up to block a shot. (Photo courtesy of St. Bonaventure athletics)

Still, Brown and his friends made the drive and arrived early. As the Bonnies did their shootaround before the game, Brown summoned the nerve to climb down to the court and say, “Hey, Bob.”

Lanier lit up. “He greeted me,” as Brown puts it, “in neighborhood fashion.”

Around Buffalo, that emotion mirrors how those who knew Lanier in childhood are now responding to his death. The way Brown sees it, the loss of his wife gave him what he calls “the made-up mind,” in however many years he has left, “to be the man she always knew that I could be” – meaning he will try to live out and pass on what is most important.

With Lanier, Brown does not think first of college heartache or the NBA. What he remembers is the jubilant Bennett celebration in 1966, when the Tigers knocked off Emerson to repeat as champions. The drinking age then was 18, and one of their teammates smuggled in a bottle of champagne.

Brown’s unforgettable first sip was just after Lanier and his teammates won it all, a taste of what he understands – all these years later – still pulls together everyone who helped to put them there.

Sean Kirst is a columnist with The Buffalo News. Email him at [email protected].