The photography book that I returned to more than any other this year was Encampment Wyoming by Lora Webb Nichols, an extraordinary record of life in a US frontier community in the early 20th century. Comprised of photographs by Nichols and other local amateur photographers, it emanates a powerful sense of place. Domestic interiors and still lifes punctuate the portraits, which range from the spectral – a blurred and ghostly adult plaiting the hair of a young girl – to the stylish – a dapper, besuited woman peering through a window. An intimate, quietly compelling portrait of a time, a place and a nascent community.

Perhaps because of the strangely suspended nature of our times, I was also drawn to contemporary books that dealt in quiet reflection. Donavon Smallwood’s Languor was created during the lockdown spring and summer of 2020, as he wandered through the woods in the relatively secluded north-west corner of New York’s Central Park. Smallwood’s images of glades, streams and ravines suggest stillness amid the clamour of the city and are punctuated by his deftly composed portraits of the individuals who were regularly drawn there during the pandemic. The book’s subtext deals with the fraught history of Central Park, a space that has often echoed the city’s racial tensions. “What’s it like to be a black person in nature?” asks Smallwood in this quietly powerful debut.

Russian-born photographer Irina Rozovsky’s In Plain Air trained her acute outsider’s eye on another bucolic New York landscape, Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, which, in summer, is a microcosm of the city’s multicultural dynamic. Again, the pandemic is the looming backdrop for these studies of people in human-made nature: walking, resting, working, playing and interacting with each other and their surroundings. A masterfully sustained study in mood, atmosphere and landscape.

A much more otherworldly landscape is the setting for another impressive debut, Speak the Wind, by the Iranian-born photographer, Hoda Afshar. She was drawn to the islands of Qeshm, Hormuz and Hengam in the strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf by an age-old local belief that the wind that has shaped the dramatic terrain is also the source of sickness and possession by spirits. Her vividly atmospheric portraits and landscapes evoke the otherness of the islands, but also suggest the invisible and intangible forces, historical and communal, that have shaped this in-between place, and helped form its customs and beliefs. An ambitious, multilayered narrative that repays close attention in its glancing approach to myth, ritual, landscape and the long shadow of colonial history.

Originally self-published in a now sought-after limited edition, Tereza Zelenkova’s The Essential Solitude is an altogether different imaginative response to a mysterious place. In this instance, the setting is the gloomy interior of a Grade II listed house in London’s East End, which belonged to the late Dennis Severs, an eccentric who styled it on his imagined idea of what an 18th-century Huguenot dwelling might look like. Influenced by often esoteric literature, from the Decadents to transgressive thinkers such as Maurice Blanchot and Georges Bataille, Zelenkova’s work is rich in symbolism and suggestion, her singular gaze capturing the disorienting atmosphere and fading grander of a house haunted by the extravagant imagination of its creator.

A sense of foreboding also attends American photographer Carolyn Drake’s mysterious Knit Club, another ambitiously atmospheric meditation on place and community. Framed as a collaboration between the photographer and an anonymous group of women, part sisterhood, part secret cult, the book is a mischievous play on the southern gothic tradition that also contains a subversive feminist subtext. Drake’s shifting narrative is borrowed from William Faulkner’s novel, As I Lay Dying, while her deftly constructed images nod to clandestine rituals and the contested history of the US south.

An often invisible US emerges powerfully from the pages of Matt Black’s epic American Geography, which was six years in the making, the photographer traversing the country by van and Greyhound bus to visit communities with a poverty rate above 20{5b4d37f3b561c14bd186647c61229400cd4722d6fb37730c64ddff077a6b66c6}. He was interested, he told me back in 2016, in “the psychology of poverty”, and he has succeeded in evoking that complex dynamic in monochrome images that are austere and haunting. The visual narrative is threaded though with his own observations, snatches of overheard conversation, and everyday ephemera encountered in bus stations, truck-stops and roadside cafes. A masterwork of contemporary documentary.

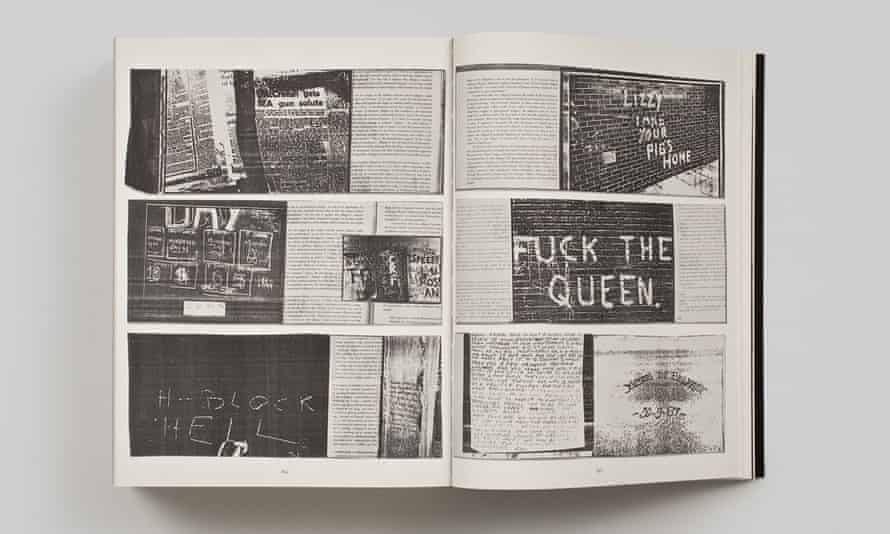

Perhaps the photography book event of the year was the long-awaited publication of Whatever You Say, Say Nothing, by Gilles Peress, a two-volume epic of his photographs from the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Structured across 22 semi-fictional days, the book is probably the most visceral, and certainly the most ambitious evocation of what it was like to live though the tumult of those violent times. What impresses above all is Peress’s uncanny ability to capture single dramatic moments – of violence, mourning, resistance, brutality – that are repeated throughout like small variations on a bigger theme of tribal and political division. The narrative is overwhelming, as it should be, and an accompanying volume, Annals of the North, provides much needed context. An immensely important book, but a prohibitively pricey one aimed squarely at the photo-book collectors market.

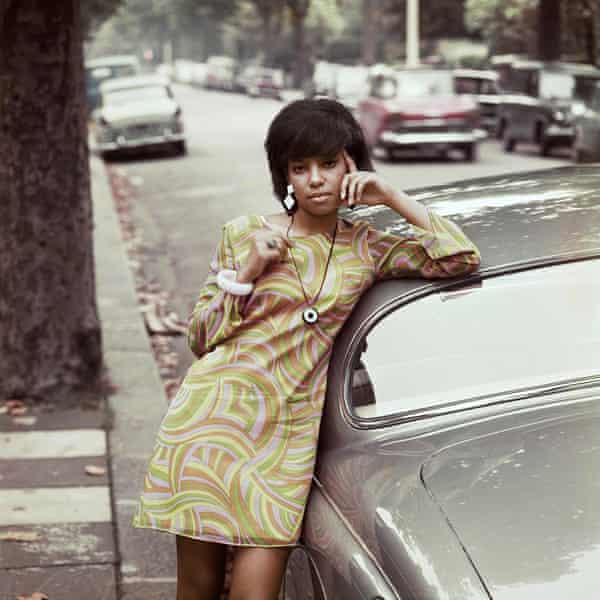

Two exhibition catalogues stood out for me this year: James Barnor’s Accra/London: a Retrospective, which accompanied the Ghanaian-born photographer’s exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery, and Coming Up for Air, which was published in tandem with Stephen Gill’s survey show at the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol. The first showed how Barnor, who is 91, moved effortlessly between genres – portraiture, photojournalism, fashion – while also creating a vibrant record of the lives of ordinary Africans in his native Ghana and the diaspora in the UK. The second was a journey inside the restlessly inventive mind of one of Britain’s most original contemporary photographers that traces Gill’s mischievously subversive gaze from inner city Hackney to rural Sweden. Both are highly recommended.

In a strong year for books by female photographers, I was also drawn to Nancy Floyd’s epic of self-portraiture, Weathering Time, which she describes as “my visual diary, personal archive, and record of my changing body and my environment over the past 30-plus years.” Since 1982, Floyd has tried to photograph herself every day, mostly standing impassively on her own, sometimes doing stuff with a dog or a family member in attendance. The book is edited from more than 2,500 images, all of which are pretty ordinary, but accrue a profound resonance when sequenced chronologically.

Finally, perhaps the most quietly resonant photo-book I received this year was Odd Time by Mirjana Vrbaski, in which a selection of austerely beautiful portraits that nod to the Dutch old masters give way to almost ghostly images of the deep forest landscapes of the Dalmatian coast. There is a strange purity to both sequences, but it is the portraits of the young women that haunt the imagination with their poise and unreadable expressions. The silence emanating from Vrbaski’s portraits speaks of a deep engagement with her subjects and invests her images with an almost unsettling presence that is hard to pin down, but extraordinarily palpable. A small, perfectly formed book in which the images speak for themselves.