Greenpeace: half a century on the frontline of environmental photo activism | Environment

Fifty years ago, on 15 September 1971, a ship named the Greenpeace set out to confront and stop US nuclear weapons testing at Amchitka, one of the Aleutian Islands in south-west Alaska.

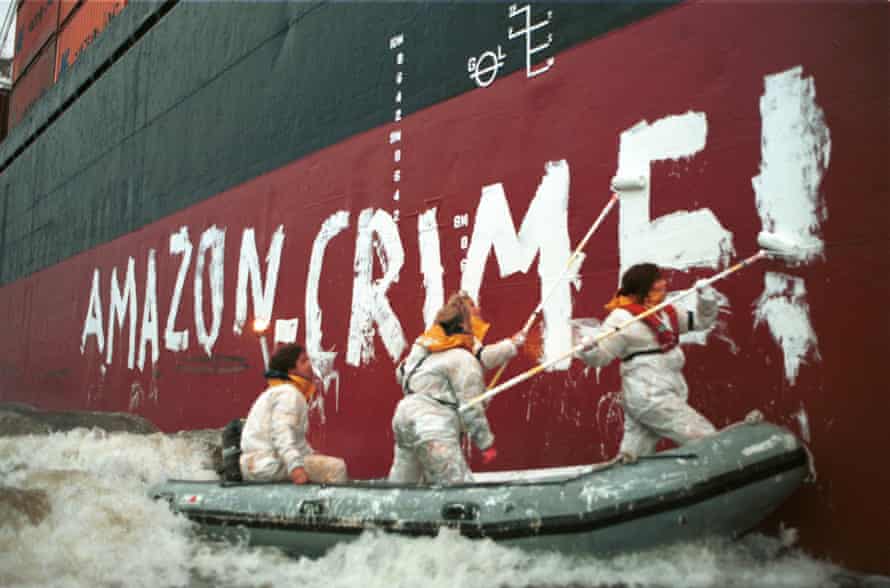

Two years later a small boat called the Vega, crewed by David McTaggart, Ann-Marie Horne, Mary Horne and Nigel Ingram sailed into the French nuclear test site area at Moruroa, French Polynesia in the southern Pacific Ocean. Photographers had been using their images for years to publicise situations around the world. But Greenpeace was a young organisation pioneering a new kind of activism: this was the moment they began to realise that capturing images of what they were doing and seeing would play a vital role in their work.

French commandos boarded the Vega and assaulted McTaggart and Ingram. However, in the confusion Ann-Marie Horne managed to get a few secret shots and was able to smuggle out the film of the incident by concealing it in her vagina. Her pictures showed the commandos armed with knives and truncheons. The pictures and story consequently made groundbreaking news, stoking the nuclear testing controversy.

After the Vega incident, Greenpeace made a pledge to photograph everything it did. It quickly learned how to harness the power and strength of emotive images bringing the world shocking scenes of seal pups clubbed by hunters and the inspirational images of activists standing up to whaling ships.

In the mid-1980s, the fast-growing organisation started to get serious about photography and needed a communications division to professionally handle the growing archive of negatives and film rushes that were being stored on office floors, plus a space dedicated to housing state-of-the-art image technology.

A film production area, picture desk and darkroom were established in London; there was equipment ranging from the early AP Leefax transmitters to cutting edge teletext machines for news updates. Film processing, printing, editing, captioning and cataloging was all done in-house by a small, dedicated team.

Greenpeace’s images would often feature on Reuters and AP, with the BBC and other influential news outlets using the images. A core team of Greenpeace photographers emerged; these individuals were professionals in the industry with empathy for Greenpeace ethics and equipped mentally to deal with the hardship of the organisation’s ambitious campaigns.

As the organisation continued to grow, newly opened national offices around the world were making images for their own national media in different, culturally sensitive styles. Actions became more ambitious and grander, with two or three photographers sometimes commissioned for one event.

In the last 20 years digital communication has transformed and turned the photo industry around. Many small agencies have not survived the changing media landscape generated by the vast consumption and oversaturation of photos available on the internet. The viewer is privileged to know more about the issue, brought closer to the reality, can interact, and play their own part in the story. Climate change, extreme weather, human displacement, political struggle and even wars can be directly linked to environmental issues and are now subjects of intensive debate.

The Greenpeace picture desks globally embrace all distribution portals – from its relationships with global wire agencies, to the established social networks, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook. Photographic technology has transitioned to digital during Greenpeace’s 50 years, yet the fundamental principle behind photo activism remains unchanged. The photographer skilfully captures a significant, controversial, and groundbreaking event and a strategic decision is made as to when and how to release the story to the world.

Through the dedication of critical ecological campaigning, the bravery of activists, the professionalism of photographers, discerning communicators and the careful preservation of the organisation’s images.

Greenpeace – the pioneer of photo activism – has remained committed to its core values of exposing environmental injustice though its imagery for the last 50 years.

-

A man attempts to rescue two oil firefighters, Zhang Liang and Han Xiaoxiong, struggling in thick oil slick, 2010