Andy Warhol as a gay artist in conflict with his Catholic faith

(RNS) — Andy Warhol’s pop-art masterpieces — paintings of Campbell’s soup cans and Brillo boxes and saturated Marilyn Monroe screenprints — deftly thrash American consumerism and celebrity culture with a cynicism carefully disguised as tongue-in-cheek. He was careful to keep his distance as a witty, shameless auteur.

The first-ever exhibition to focus on the legendary artist’s Catholic faith at the Brooklyn Museum, “Andy Warhol: Revelation,” sits in stark contrast, almost as if displaying an entirely different artist.

Warhol is still plenty tongue-in-cheek: The exhibition opens with “Raphael Madonna — $6.99,” a floor-to-ceiling painting of Madonna and child overshadowed by a bright red price tag. Warhol, the former graphic artist, sketched advertisements for a Jesus nightlight and, in collaboration with Jean-Michel Basquiat, painted Jesus on a series of punching bags in “Ten Punching Bags (The Last Supper).”

But the exhibition’s focus on the artist’s faith touches on the conflict, and sometime the horror, of being a gay man in a tradition that deeply disapproved, and adds dimension to what we know about Warhol’s relationship with his mother.

ARCHIVE: Dissent from Traditional Plan dominates United Methodists’ top court meeting

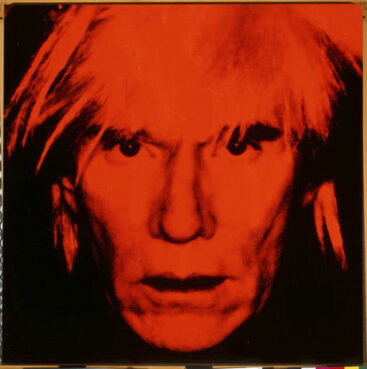

Andy Warhol (American, 1928–1987). Self-Portrait, 1986. Acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen, 40 × 40 in. (101.6 × 101.6 cm). The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., 1998.1.821. © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Warhol, born Andrew Warhola, was the son of Slovakian immigrants and grew up in Pittsburgh attending St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church. The Byzantine Catholic tradition is one of 23 autonomous churches with allegiance to the pope in Rome while retaining Eastern, or Orthodox, Christian traditions. Warhol’s childhood church followed the specific ethnic traditions of his parents’ Rusyn heritage.

Warhol would maintain a shifting relationship with the church until his death in 1987. He attended three different Catholic churches in New York City, with his mother or alone, and received a traditional Byzantine Catholic funeral. Along with these works, the exhibition includes several personal artifacts — like crucifixes from Warhol’s home and other religious belongings — documentation of his meeting with the pope and more.

His Catholicism is a rarely discussed inspiration — perhaps because his Manhattan studio, The Factory, was a safe space for same-sex relationships and transgender people, as well as nudity and sex and drug use. It seemed to be anything but pious.

But a tragic sense of repression pervades the show. Warhol, whose own sexuality was nearly as tightly held as his religion, often represented his conflict with his own physicality, as in the version of “Be Somebody With a Body” that appears in Brooklyn. The black-and-white painting, from 1986, lifts an image from a muscle magazine depicting a buff bodybuilder but superimposes a Renaissance Jesus.

Installation view, Andy Warhol: Revelation. Brooklyn Museum November 19, 2021-June 19, 2022. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum. Artworks by Andy Warhol © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Used with permission of @warholfoundation)

Though these introspective images from his late career have been called cryptic, in the context of the show, “Be Somebody with a Body” comes across as the work of a man in anguish. Immediately beside it is a photograph of Warhol with his torso as bare as the bodybuilder’s but marred with scars from the gunshot wound he suffered in the attempt on his life in 1968.

Warhol’s recreations of Renaissance paintings also express a quiet yearning for touch and companionship, something he suggests he may have been in ways deprived of. In Warhol’s version of “The Annunciation,” the hands of Gabriel and Mary are the only physical features depicted. It feels much less of heavenly royalty and much more of earthly longing.

Andy Warhol (American, 1928–1987). The Last Supper (Detail), 1986. Screen print and colored graphic art paper collage on HMP paper, 31 5/8 × 23 3/4 in. (80.3 × 60.3 cm). The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., 1998.1.2125. © 2021 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Perhaps the most precious of them all is a detail of Leonardo Da Vinci’s “The Last Supper,” a painting that became a fascination in the 1980s and which some critics have connected to Warhol’s response to the AIDS epidemic. He began his series on “The Last Supper” after the death of his companion, Jon Gould. Warhol isolates pairs of apostles from the table, introducing a soft tenderness. John and Peter interact in what suddenly appears an embrace between friends or lovers.

These almost inward explorations of love and faith convey a fascinating and fleshed-out portrait of Warhol as an artist and as a man caught between his Catholic faith and his queer identity.

The exhibit will be open in the Brooklyn Museum until June 19, 2022.

(Editor’s note: This piece has been updated to reflect a correction of Marilyn Monroe’s name.)

![[BN] Photography: Covering the Bills | [BN] Photography: Covering the Bills |](https://bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/buffalonews.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/9/5b/95b78dc2-4953-11ec-8a55-af4be2958196/6197cd14707c6.image.jpg?crop=1600,900,0,49&resize=1120,630&order=crop,resize)