Patti Smith: ‘I am who I am with all my flaws’ | Patti Smith

It is mid-morning outside the Pompidou Centre in Paris and Patti Smith is talking to me on the phone – she is trying to puzzle out how best we are to find each other within the labyrinthine building: she is somewhere inside working on an exhibition, a sound and visual montage of three French poets: Arthur Rimbaud, Antonin Artaud and René Daumal.

At 75, she is the figurehead of American punk – her 1975 album, Horses, has often been selected as one of the top 100 albums of all time – and with each year that passes, she becomes more age-defyingly remarkable. She spent much of last year touring and continues to work as a poet and artist – her memoir, Just Kids, about her relationship with the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, won the 2010 US national book award.

Having interviewed her on the phone in 2020, I already know she has an extraordinary ability to stay naturally herself (the explanation that she will send an assistant curator to meet me because she has “no sense of direction” is not disingenuous). And now the assistant curator is leading the way up the escalator and into the exhibition space and I see her at once, deep in conversation with Soundwalk curator/director Stéphan Crasneanscki, considering a collage of photographs, her back facing me, talking about the extra space needed to allow her chosen artists to breathe.

-

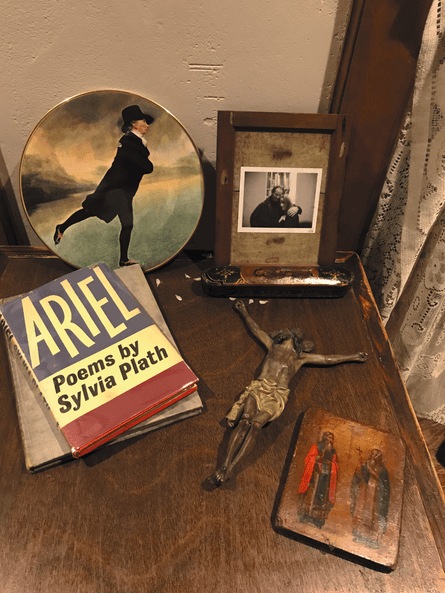

8 January

‘As a young girl, I admired the skater’s attire, eventually adopting the look as my own. The plate belonged to my mother who always tried to make me wear bright colours. The skater won out. He dwells beside my copy of Ariel, given to me by Robert Mapplethorpe in 1968.’

Allowing artists to breathe is Smith’s forte – she is never more herself than when celebrating others – and our reason for meeting is A Book of Days, her beautiful new collection of 366 captioned images, one for each day of a leap year. The book includes black-and-white Polaroids from her archive and images from her Instagram account (she has more than 1 million followers) and is, in common with the Pompidou show, a work of creative homage to writers, poets, friends and family. As she turns around, she is all apologies and politesse. She is small for someone with such presence. She has the face of a dreamer – warmth mixed with distance. An unsecured plait, no wider than a shoelace, is starting to unravel in her long grey hair. She wears mannish specs and a mustard-coloured suede shirt thrown over a worn T-shirt – I cannot make out its psychedelic text. Her trousers are black and her neat riding boots decorated with a suggestion of gold spurs. You might read her as distraite but actually I’d say she is concentrated.

We have to take the escalator back down to the Pompidou’s basement to find an empty conference room in which to talk, and we sit side by side on a sofa. She tells me how she first got on to Instagram as a bid against inauthenticity: “My daughter, Jesse, told me that because I wasn’t on Instagram, it was an open field for impostors who were exploiting and soliciting other people in my name and I said: ‘What can I do about it?’” Jesse told her how to open an account, get verification: “‘All you have to do is to choose a picture, then write a little message to the people.’” Since then, she has used Instagram as a force for good and feels she needs it to be “part of society”. She calls her account This is Patti Smith. Her Instagram – and the book – are inclusive, reaching out to readers in a shawl of words: “Birthdays acknowledged are prompts for others, including your own,” she writes.

While A Book of Days is dedicated to others, its cover is of Smith in a dashing, black, wide-brimmed hat carrying a Polaroid 250 Land Camera that now looks quaintly retro with her hand irresolutely over her mouth – reverie second nature to her. Its first image is of her hand raised in greeting. “HELLO EVERYBODY”, she exclaims. Hands appear throughout her books, in and out of dreams. Could we focus on her own? Surprised, she considers them: small, shapely, barely lined. Does she ever look at her hands and think: you’ve been with me through everything? She laughs, surprised: “Gosh, yes, I do think that. I look at them and see my whole life. I realise I’ve not changed all that much. I’m just older, older, older…” She feels particularly in touch with her 11-year-old self, “running through fields with my dog and free of social conformities”.

I ask if she has ever had her palm read and she tells the strangest tale. She was born during a hurricane, in Chicago, in 1946, and raised in Germantown, Philadelphia. Her father was a machinist, her mother a waitress who took in ironing. Her mother had a co-ironing friend, “a big, beautiful black woman I called Aunt Novella”, who one day took her to the zoo: “As we were walking, a Gypsy fortune-teller grabbed my hand, looked at my palm and went: ‘Ssssss…’ She made a sign like a cross, looked very disturbed and sent me away. I asked Aunt Novella: ‘Why did she do that?’ And she replied: ‘She is afraid of you.’ I was only six years old. It made me think: does she think I’m bad? It made me feel very strong – I’ve kept that in myself ever since.”

Smith has needed strength – of which more later. But on the subject of her book: when you look through it, you will find tributes to Murakami, Camus, Kurosawa and Martin Luther King before you have even reached the end of January. And it is intriguingly furnished with photographs of writers’ beds: Virginia Woolf’s with embroidered bedspread (25 Jan), Georgia O’Keeffe’s with a more humble covering (6 March); Frida Kahlo’s with a spooky black skeleton above it (6 July); John Keats’s, which “seems to contain the luminous dust of his consumptive nights” (3 August); and a snap of her own single bed in her house on Rockaway Beach, with a stout pillow (15 March).

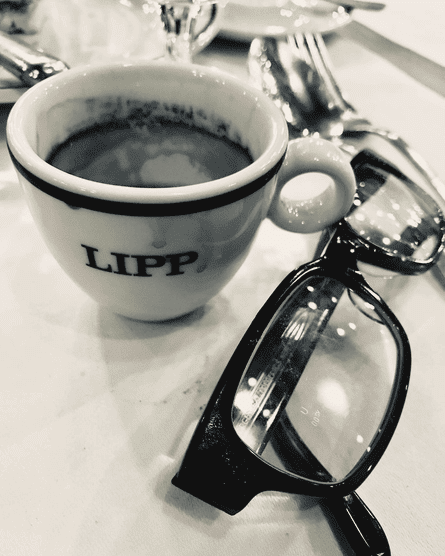

I see her as a literary pilgrim, I tell her, and she looks pleased. But what I most want to know is why she is so dedicated to celebrating other artists? She replies simply: “Because they magnify my life.” From childhood onwards, she has wanted to “thank” artists. And this makes our meeting in Paris especially fitting because of her joy at the way the city salutes artists and writers (just think of the street names). And as she continues to love France, the French return the compliment: the ministry of culture made her a commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2005 and, in May this year, she received France’s highest accolade when she was made an officer of the Légion d’honneur. Paris recurs in A Book of Days – as it has throughout her life. A black-and-white snap of a coffee cup from Brasserie Lipp alongside her spectacles (10 March) has the caption: “All I needed in Paris.” There are snaps of the Seine and the English bookshop Shakespeare and Company. When she first came to the city, in 1965, she sang on its streets, an unknown, between La Coupole and Le Dôme, and remembers the actor Leslie Caron passing and slipping 20 francs into the hat. From the first, she was “drawn to French culture in every aspect from Jeanne Moreau to Genet”.

Her love affair with 19th-century French poet Rimbaud has also lasted: “I was 15 when I found a copy of Les Illuminations with Rimbaud’s face looking very Bob Dylanish and thought: that’s the poet.” In 1974, she visited his grave in Charleville and found it “overgrown with cabbages – he’d fallen out of favour”. Today, she not only champions his poetry but finds herself guardian of his house in the Ardennes (22 Oct). Rimbaud’s mother’s family offered it her. “Rimbaud finished A Season in Hell there in 1873.” The house was bombed during the first world war and rebuilt. “It’s very nice now – I’ve cleaned it up, refurbished it, got new sewage. My desire is to make it a poets’ residence for short periods. But the real value of the place is the land itself. This is where Rimbaud lay down at night… looked up at the stars… maybe took a piss… it’s his family land.”

A Book of Days is personally devotional too. It practises (to borrow from the poet Elizabeth Bishop) the art of losing. “By the time I was 46, I’d lost my pianist, Richard Sohl, who died at 37 (26 May), and to whom I was very attached; Robert Mapplethorpe, who died when he was 42 (1 September); my brother Todd (15 June), who died at 42 [he had a stroke while wrapping Christmas presents for his daughters]; and my husband, Fred Sonic Smith [a guitarist with radical band MC5], who died at 45 (14 September).” She recalls their first meeting: “I met Fred in Detroit. There was a party for my band, in the afternoon, in a famous hotdog place: the Lafayette Coney Island. I don’t like parties so much but I had my hotdog and was about to leave and saw this fella standing against a wall and I was struck by him. And that meeting, probably more than any other, changed my life.” One day – she is not ready yet – she will write about him. “He was the love of my life.”

“In a succession of losses,” she continues, “you start to understand the process and yet each loss takes its individual toll. All loss is something we know we’re going to suffer and then life moves along… things seem OK… then, one day, you’re walking down the street and the pain of a loss that happened years earlier will come back at full capacity.” When ambushed by grief, she tries to “ride it out. Sometimes, it can be so intense, you have to train yourself not to be enveloped by it. You don’t want to fall into the abyss.”

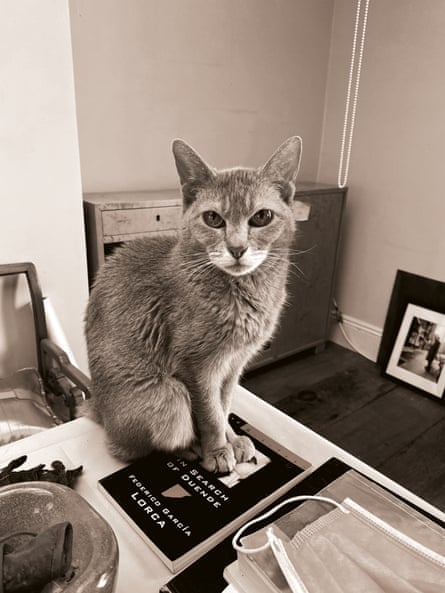

Abyss-dodging means developing a sustaining routine. And she explains that her cat plays a leading role in her New York life. Cairo is a 21-year-old Abyssinian with an uncompromisingly feline stare pictured atop a book of Lorca’s, calling a halt to any possibility of reading on (5 June 2018). “I get up early and feed her. I give her water. And I drink hot water with lemon. Then I go nearby and have a coffee and take my notebook and a book. I like to make the morning my writing time but if I can’t write, I’ll read and often the reading will inspire me.” Cups of coffee in her books become almost talismanic, as do preferred foods: fresh rolls, anchovies packed in salt, fresh mint – all key ingredients. Her routine began when she had her son, Jackson, in 1982: “Having a child… you are no longer the centre of your universe,” she laughs. She has a wonderful, radiant, crooked smile and, when it comes, laughter like a sudden thaw. At the same time, I note that the laughter is seldom mischievous, somehow serious. As a writer, she volunteers, she spends most of her time alone.

-

26 July

‘Sam [Shepard]’s Adirondack chairs in Kentucky. We would drink our coffee, talk about writing, or just watch the sun go down in comfortable silence.’

She must sometimes get lonely? She does, she says. But more often, she gets restless. As a person, and a writer, she travels light. A picture of her old travelling boots bears the caption: “Time to get moving” (6 September). I imagine her recent tour must have been exhausting? “It did take it out of me. This year has been tough, trying to make up obligations cancelled in 2020 and 2021.” Next year, she plans to focus more on writing and a new recording: “I’m going to simplify my life.”

Simplifying might prove a challenge. She describes herself as a “messy minimalist” and confesses books overwhelm her New York home (only a literary burglar would know what to steal). Her beach house, her “Alamo”, is “a respite from clutter” – an elegantly spartan shack that survived a hurricane and is filled with gifts: an Italian desk from Johnny Depp, a Brancusi self-portrait from Michael Stipe and Giuseppe Verdi’s calling card – a gift from her daughter. Her entry for 28 January reads: “Keep on going, no matter what, my talismans seem to whisper.” And she writes often about the pain of losing things. In her memoir M Train, she entreats her objects: “Please stay for ever.” And now she singles out some mysterious losses: a heart-shaped necklace made for her by Mapplethorpe, a book about Paris and Vienna with her mother’s maiden name inside, and recalls how her husband gave her “a little silver bar. I always put it – we were parted a lot – under my pillow, wherever I was. One day, I forgot to retrieve it… it wasn’t valuable but he had given it to me.”

There is something of that silver bar about Patti Smith – a shining resistance, a knowing of her own mind but tempered with kindness. She is, one suspects, not unlike her mother, whom she recalls with staunchest affection. “My mother was very down to earth – with a good strong sense of self. She loved performing and had a beautiful, clear singing voice. She came to my concerts until she was 80 years old.” She was “thrilled” by her daughter’s success. “My parents had no prejudices. I was brought up in a completely open way in terms of religion, race, gender… The only criterion was you had to be a nice person.”

Her upbringing fortified her and, perhaps, her unworldliness too: Smith might have been at home in another century. She does not know how to drive and nor, in spite of her love of the ocean, to swim. In Just Kids, she writes about how, unlike many of her generation, she always avoided drugs: “I was a sickly child: I was born with bronchial pneumonia, I had tuberculosis, scarlet fever… my mother spent a lot of time helping to keep me alive – and, by 20, I’d gone through a lot physically. I never considered I’d have a long life because I’d battled so many illnesses and decided I was not going to throw my life away.”

Coming to the Chelsea hotel, aged 22, she found it filled with people “already damaged by drugs”. And there was another reason to resist: “I like my mind. I have an intense imagination. I like to be in control of my own state.” But there must have been pressure to join in? “I’m not one to succumb to peer pressure,” she replies.

Given that Smith’s work is about affinities, it is no surprise many fans think of her as a friend. Does she ever pine for anonymity? “Yesterday, I was in the museum walking around and so many young girls were just saying hello, taking my hand, speaking to me. To feel love from young people is a wonderful thing.” She feels “anonymous and loved” in Paris. She adds: “I try to encourage people who feel I’ve been important to them. If somebody says, you changed my life, I’ll say, I hope for the better, but you’re going to keep going. I thank them and try to remind them that I’m just a stepping stone to themselves.”

Rereading Just Kids, the sense is that her own life unfolded with serendipitous effortlessness: Mapplethorpe rescued her from an unwelcome date. The poet Allen Ginsberg was randomly encountered in a launderette; she walked out with the playwright Sam Shepard with no notion of who he was. She even appeared to become a rock star by accident. Does she believe in fate? She replies that, when younger, she saw life as a “huge prayer rug where the threads make a beautiful design but with intentional flaws”. She is still drawn to the “grand design” even if the carpet is a comforting fiction.

-

22 October

‘Chuffilly-Roche. The Rimbaud family compound was bombed in World War I, then rebuilt from the rubble. The house sits on the same land where they harvested corn and the poet wrestled with A Season in Hell. The plaque attached to the stone façade reads: At this place Rimbaud hoped, despaired and suffered.’

She also believes in free will. “I believe in everything simultaneously. I don’t have a religion and don’t need one.” Like most of us, she worries about the world. “Today, I woke at four in the morning out of a sound sleep, thinking of the women of Iran and of my daughter… my mind all over the place. I keep waking through the night. Part of me is always conscious of what is happening in Ukraine, the threat of nuclear weapons, the climate crisis, a part of Florida destroyed.” I look at her face – tired, I see that now: “All these things radiate from my mind and I can’t… we’re powerless to take care of everything but I try to keep these people in my consciousness just as I keep the dead in my consciousness. My father, my mother – I think of them. I can’t help all the women in Yemen watching their babies die of starvation. I can only radiate love toward them. I have to, as an individual, continue to do my work. I have to find a way to balance our troubled world with my own optimism, joy and obligations. So it is always on my mind and it’s complicated.”

Work is essential to her: “When people ask whether I’d like to be called a singer, songwriter, artist or poet, I say: if you call me a worker, you’ll encompass everything I do.” Does she think about her own mortality? “I’ve always been a youthful person. I never thought about death until I turned 70. I wouldn’t think about it if I didn’t have children. But they lost their father so young. And my relationship with my children is so strong [Jesse and Jackson are musicians and recently accompanied their mother on tour], I hate the idea of leaving them.” But her emphasis is always on life: “I just keep doing my work, try to take care of myself. I feel blessed to have the imagination I have but don’t think it makes me more important than anyone. I am who I am, with all my flaws – and I’m grateful.” And with the same courteous attention she has brought to our conversation, she now explains she must change for the photographer – all she needs is her black jacket, she says, and she will be ready.

A Book of Days by Patti Smith is published by Bloomsbury (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/3LNE3G5BAJIPZBIKOC3PG4ILRI.jpg)