‘My life is weird’: the court artist who drew Ghislaine Maxwell drawing her back | Life and style

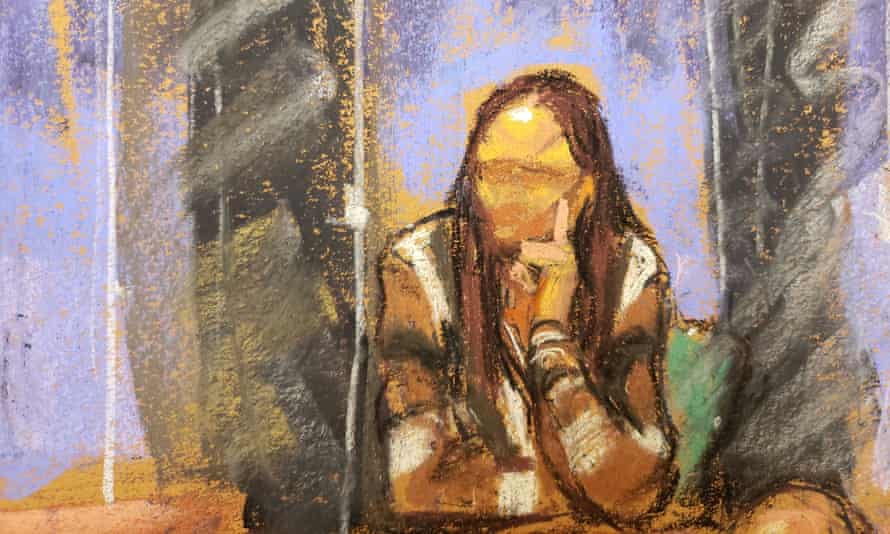

Pastel drawings don’t typically go viral on the internet. But this month, thousands of Twitter users were mesmerized by a courtroom artist’s sketch of Ghislaine Maxwell – the alleged sex-trafficking accomplice of Jeffrey Epstein – staring at the artist and sketching back.

Twitter users were disturbed. “I thought this was funny at first but it’s starting to haunt me,” one person wrote. Others commented on the picture’s bizarre, recursive quality – reminiscent of MC Escher’s drawing of hands drawing hands, and raising the possibility of some kind of infinite loop. Was Maxwell trolling us? Or sending the artist an ominous message?

“I don’t know, and I’m not going to try to read her mind,” Jane Rosenberg, the artist in question, told me. “Maybe she was just bored coming out of her jail cell. I know her sister sometimes also sketches in court. Maybe the Maxwell family just likes to sketch in their free time.”

She and another artist, Liz Williams, were sketching Maxwell one day during a pre-trial motion when they noticed that Maxwell, armed with a pen or pencil, was returning the favor. She and the British socialite have since become “sketching buddies” of sorts, Rosenberg says. Maxwell waves to her sometimes. Once she mouthed something, and Rosenberg realized she was saying: “Long day, isn’t it?”

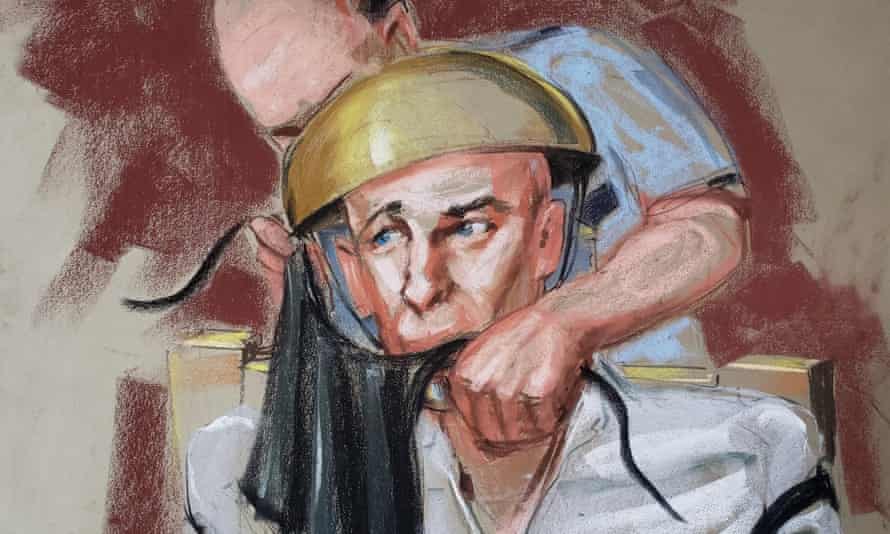

For Rosenberg, it was, in fact, just another long day as a member of one of America’s most rarefied and unusual occupations. In more than 40 years as a professional courtroom artist, she has covered the trials of some rather “bad guys”, including the drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán; the celebrity sex criminals R Kelly, Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby; the World Trade Center and Boston marathon bombers; Mark David Chapman, assassin of John Lennon; the mobster John Gotti; the police officer Derek Chauvin, who killed George Floyd; and the fraudster Bernie Madoff.

If there was a major trial in the last four decades, there’s a high chance Rosenberg was watching from behind a sketchpad. Sometimes, her subjects offer unsolicited feedback. “John Gotti wanted his double chin removed,” Rosenberg told the New York Post last year. And people “always want more hair. I get that all the time.”

Although some state courts now televise trials, American courts have historically resisted allowing cameras – because photography is considered distracting, and can turn courts into media spectacles, and because of the risk of compromising the identities of jurors or protected witnesses. (New York permits photography on a case-by-case basis, but federal courts strictly prohibit it.)

When courtroom artists sketch jurors or sensitive witnesses, they often leave their faces blank. Rosenberg’s illustrations of the Maxwell trial and other cases include poignant portraits of anonymous witnesses with ghostly, blank faces, their features sometimes further obscured by hands clutching tissues.

Courtroom artists believe that hand-drawn art is more forgiving than photography, and potentially less lurid; it also has the advantage of artistic license – artists can compress people and action into a single frame, conveying a sense of courtroom drama and atmosphere that is difficult for still photography to capture.

The job demands a brutal schedule. Rosenberg, who lives near Columbia University with her husband, a criminal defense attorney she met at a courthouse, wakes at 4am most days in order to get ready for court and arrive in time for good seating. When she’s not at court, she’s on call – arrests or arraignments can be announced at any time, and media organizations often contact her at the last second – so, like a country doctor, she always has her equipment case ready and waiting next to her apartment door. Her kit includes prescription binoculars and finger cots, the small latex thimbles that protect her hands from drying out.

Every night when she gets home, she spends at least half an hour cleaning her equipment and ordering pastels to replace those worn down to quarter-inch stubs. When I spoke to her on the phone, she had just finished sorting and discarding “a million tiny lumps of black”. She has to work in daylight or she can’t see the colors accurately.

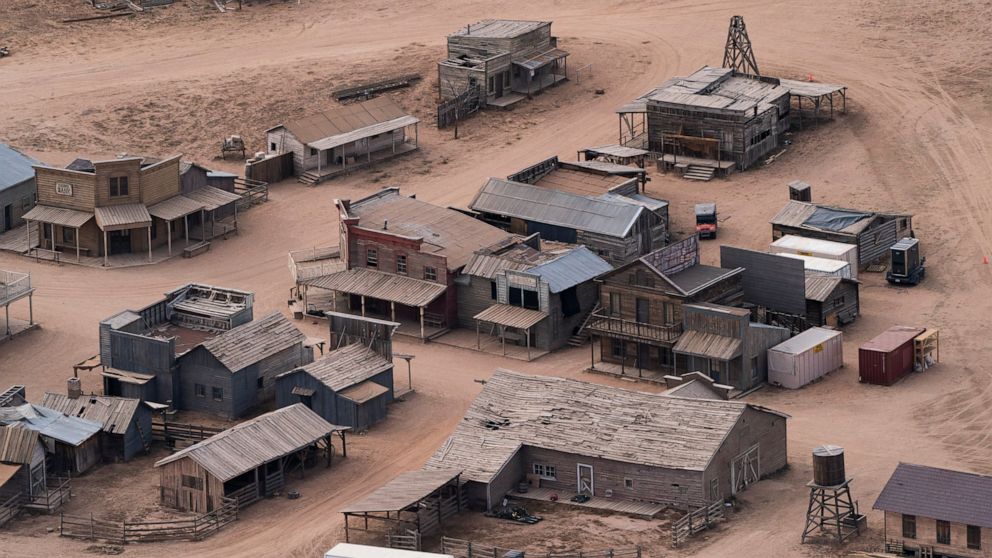

Arraignments are particularly stressful, because of their brevity – a courtroom artist must race to capture the defendant in a few deft lines as they plead guilty or not guilty. In some big trials, artists are relegated to an overflow room and have to watch through video monitors. During pre-trial motions in the Maxwell case, Rosenberg was able to sit in the empty jury box and watch, with rare proximity, as Maxwell shuffled into the room in shackles – greeting people and exchanging pleasantries, and sometimes kisses, with them.

Rosenberg sometimes covers trials in other states, but travel is unpleasant. “It’s hard to fly with my pastels,” she says. “I can’t check them – they’ll all get broken – and when they go through a metal detector they kind of look like bullets.”

When she was in college studying art, abstract artists such as Willem de Kooning and Alexander Calder were in vogue and portrait painting was regarded as embarrassingly passé.

“I just never knew how I was going to earn a living. I struggled for many years,” she says. “I did chalk drawings on the sidewalk, copying Rembrandts and Vermeers, with the hat out for money. I did pastel portraits for tourists in Provincetown, Cape Cod.”

One day, she attended a lecture by a courtroom artist at the Society of Illustrators in Manhattan. She was intrigued, and decided to try to break into the niche industry. “I didn’t think I was good enough, or fast enough, but I knew I loved drawing people.” She began hanging out at courthouses, building a portfolio (“I spent a lot of time at night court, drawing prostitutes”), and eventually sold a sketch on spec to NBC.

Since then, she has usually had more work than she can handle. Yet anxiety about job security is a feature of the industry. “Since I became a courtroom artist, I’ve always thought cameras are going to be in court any minute. And they did pass a bill in 1988 to allow cameras [in New York state courts], and I thought, ‘That’s it. It’s all over for me.’ However, it didn’t hold true in all New York state cases,” and federal courts show no signs of changing.

“So I continue to work. There were a lot more courtroom artists back when I first started. At the Westmoreland trial” – an explosive libel case in 1982 – “I counted about 17 artists. Each TV station had their own artist, each magazine sent an artist. Now there’s about five in New York City. We don’t all survive what’s going on with wire services and social media; it’s just a different world now.”

Each courtroom artist works in their preferred medium – some use watercolor, or oil crayons, or colored markers or pencils. Like members of any small and unusual industry, the artists share a quiet camaraderie, which extends to the other court regulars, like courtroom officers, clerks and reporters. Many have known each other for years.

Rosenberg tries not to speculate about the outcome of trials before she’s heard the defense, and to bear in mind that defendants are innocent until proven guilty. She approaches trials with a sense of professional remove, and she’s usually too focused on sketching to feel emotionally or morally stirred. There are exceptions, though, such as the trial of Susan Smith, a South Carolina woman convicted of drowning her children, whose deaths the court testimony described in excruciating detail, or a case involving a woman from Rosenberg’s neighborhood who was raped and tortured by a home invader.

“I try not to have emotion, because tears falling on my pastels is not good. But I hear horrific things a lot, and I’ve seen a lot of crime scene photos. Sometimes it gets to me, even when I’ve tried to be neutral. My life is weird, I guess. Forty-one years of seeing bad guys and bad things happen.”

On a rainy, thunderstorm-filled night in 1983, she sketched the last moments of John Evans as he was electrocuted by the state of Alabama. Evans, the first person to be put to death in Alabama since the supreme court reinstated capital punishment in 1976, had waived his appeals and demanded to be executed. It was a gruesome debacle. He was electrocuted three times before he died. Rosenberg was traumatized, and it turned her against the death penalty. “I felt like my hands were dirty,” she says.

In addition to her court work, she sells fine art, mainly plein air cityscapes in oil. She doesn’t have much time to devote to it, however, and rising crime in New York has made the prospect of painting for hours in public riskier. “I feel my neighborhood’s not as safe anymore, and I don’t feel comfortable getting absorbed in a canvas. I have to keep my eyes open and my ears alert.”

As our conversation wound down, I remembered a crucial question I wanted to ask Rosenberg: was Ghislaine Maxwell’s art any good?

“I did go running up to her lawyer after the first sketch,” Rosenberg says, “and I said, ‘Well, what does her sketch look like?’ And the lawyer said, ‘Oh, Jane, you know I can’t tell you that.’”