In living colour: the forgotten photographs of Werner Bischof | Photography

A concealed treasure trove of formerly unknown colour photographs by Werner Bischof, a person of the towering figures of 20th-century pictures and reportage, has been uncovered in Zurich bringing a new dimension to his work and introducing amazing depictions of Europe and further than.

About 100 colour prints from original negatives, some rediscovered but most under no circumstances viewed ahead of, taken by Bischof among 1939 and 1954, have been restored and function in an exhibition discovering a very little-recognised element of his imaginative output.

The photos include amazing sights of a bombed-out Europe, including the ghostlike spoil of the Reichstag building and skeletal cityscapes of Warsaw, Berlin and other metropolitan areas. There are intimate portraits of women of all ages sorting by rubble, young children participating in in the ruins of bombed residential spots and a Dutch boy whose facial area has been scarred by a German booby lure.

There are also visuals from Bischof’s lengthy excursions to Asia, North and Latin The us, concluding tragically in Peru wherever, aged 38, he was killed in a auto crash in May perhaps 1954 en route to check out a goldmine.

Very best recognised for his black and white illustrations or photos, Bischof, who joined the images cooperative Magnum in 1949 as its sixth member, went towards the grain by pursuing his enjoy of color at a time when it was broadly frowned upon amid his contemporaries, who considered it as minimal a lot more than a seductive tool for the marketing sector that assisted photographers pay the expenditures.

The visuals had been found out four many years back following his son Marco, who curates the Werner Bischof archives in Zurich, arrived throughout boxes made up of hundreds of glass-plate negatives.

“It was strange at 1st simply because we appeared to have 3 black and white identical negatives of every single graphic,” he told the Guardian. “Only on a nearer appear you see they are each a little bit various. We consulted specialists, and embarked on the really technological and subtle restoration method.” Applying scanning gear that authorized the plates to be viewed as a single complete, the images arrived alive. “It was magic, like the result you have when you make a black and white print by placing it into the developer. Besides it was color,” he suggests.

He and the restoration crew used a number of many years building the negatives and obtaining the correct colors utilizing pigment technologies, right before printing them on cotton paper.

They are on display at the Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana (MASI) gallery in Lugano, Switzerland, under the title Unseen Color. MASI’s director, Tobia Bezzola, has identified as Bischof’s oeuvre “a vigorous and fantastic incomplete chapter”. The photographs vary from the “spirited and lurid to gentle watercolour characteristics, from rococo playfulness to the aggression of pop art”.

Marco Bischof describes the act of getting the images that emerged – from psychedelic styles and polar bears to steelworkers and cats, the war-ravaged Tiergarten park in Berlin, to butterflies and a bicycle in the bombed-out shell of a dwelling in Italy – “like diving underwater and identifying a treasure trove”.

Bischof was just four several years aged when his father was killed. His mom, Rosellina, also an achieved photographer in her personal ideal, gave delivery to her 2nd son, Daniel, 9 days after her husband’s demise, on the pretty day the information of it reached her.

“She told me Papa had stayed with the Indians in Peru,” Bischof recalls. “That’s what we considered for decades.

“He was often travelling so I only put in a number of months physically in the same place as him when I was pretty small and he experienced appear residence for about 4 months in 1953. So I only seriously know my father by means of his do the job,” he suggests. “His photographs, which have been in all places around our flat, were being like great friends to me when I was escalating up. So to suddenly see a total new aspect of his pictures is practically nothing fewer than getting a new part of him.”

Werner Bischof employed three cameras: a Rolleiflex, a Leica and, far much more uncommon for the time, a Devin Tri-Coloration digicam, with which he’d experimented through the war yrs in his studio, primarily for nevertheless existence, and, having mastered the technologies, took it with him on journeys by postwar Europe. The cumbersome contraption was lent to him by the Zurich publisher Conzett & Huber, an global chief in the discipline of colour gravure, which utilised the illustrated magazine Du as its calling card. Bischof was assigned to furnish the magazine with colour photos.

Despite the fact that unwieldy and slow the Devin was technically superior compared with earlier colour cameras. It permitted a person-shot illustrations or photos for the first time.

“The digital camera was made more or a lot less just for still pictures, so he experienced to prevent movement as significantly as probable and to stabilise it by hand or tripod,” claims Marco Bischof. “He experienced to take into account his composition in advance and to have very good light-weight.” The ensuing shots, Bischof states – owing to the glass remaining additional stable than celluloid – have “incredible resolution. The more substantial you blow up the print, the a lot more element you see. They also have a selected alluring slowness in contrast to black and white.”

For the duration of the six months Werner Bischof expended travelling as a result of Europe in 1945 and 1946 capturing the consequences of war, to start with on a bicycle, then in a car or truck with in-designed darkish room, his inclination to use colour film came to the fore whenever he felt it would serve his subject superior than black and white. In the Dutch town of Roermond in 1946 he came throughout a boy identified as Jo Corbey, whose face experienced been badly hurt by a pencil-sized booby lure remaining by German soldiers. In his diary Bischof described the boy’s “blue-violet burn marks from the shrapnel, a glass eye and a purple mask, the tender crimson flesh a cruel contrast”. The picture appeared on the front protect of Du’s May 1946 edition, together with an charm: “Help the Kids of Europe”, provoking a solid response from visitors.

Marco Bischof, who is a movie-maker, speaking from his studio in Zurich, the partitions of which are full of his father’s black and white images, states he believes his father’s enjoy of colour photography had significantly to do with the reality he experienced originally preferred to be a painter and seen it through the eyes of an artist for whom colour was a kind of authentic inventive expression. But his ideas to go to Paris and set himself up in a painter’s studio experienced been dashed by the war. In a letter to his colleague Robert Capa – who was killed just nine days just after Bischof – he wrote: “In my coronary heart I will often be a painter who sees past matters in colours, who is constantly in thrall to the abundance and richness of ways humans categorical on their own and who normally sees the camera’s limitations with a tiny melancholy.”

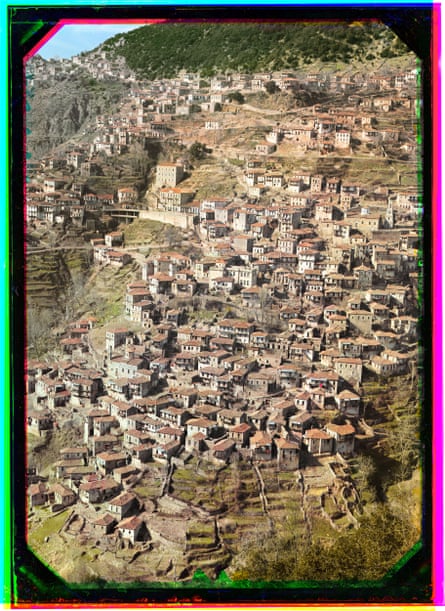

Marco Bischof has returned quite a few periods to the ravine in the Andes wherever his father died. He claims not to have a favourite impression but has tried to retrace his footsteps to find out for himself the locations where by the pictures were taken, together with the village of Kalavryta in the Peloponnese, its tightly knit redbrick houses and farmsteads nestled with each other on the hillside appearing to defy the that which took spot there in December 1943. “You believe to your self ‘what a really village’, but then you learn it is the website of one of the most cruel massacres carried out by the Nazis, killing just about the overall male inhabitants and you see it absolutely in different ways. This is typical of my father – combining variety and articles in this way.”

He’s also been on to the roof of the Swiss embassy in Berlin from the place he thinks his father captured the ruins of the Reichstag. “In that graphic it gets to be not only an amazing monument of the time, surrounded by destruction, but it appears to be like a monster by some means – a remembrance of a awful war and almost everything that took place as a consequence of that,” he suggests.

He says he still has 60,000 undeveloped negatives in the archive. “So there may perhaps however be additional surprises to come.”