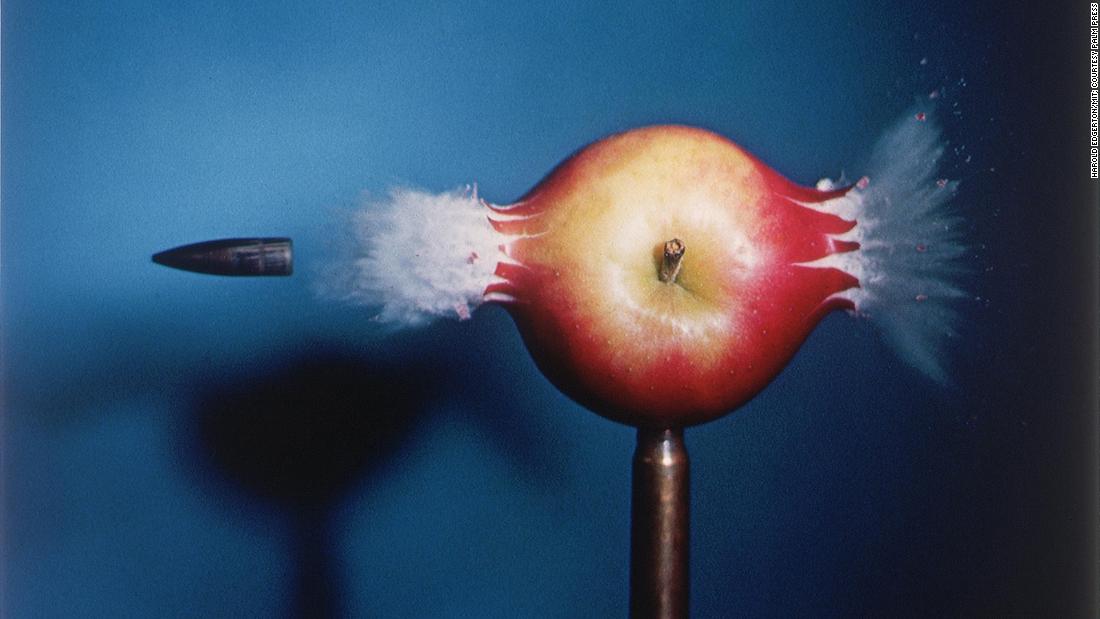

How Harold Edgerton’s ‘Bullet through Apple’ made time stand still

Exploding with vitality but correctly still, Harold “Doc” Edgerton’s 1964 image of a .30-caliber bullet ripping via an apple showed an normally unseeable instant in fascinating detail. The scene took on a serene, sculptural beauty as the disintegrating apple’s pores and skin burst open in opposition to a deep blue backdrop.

Edgerton, who died in 1990 aged 86, is considered the father of superior-pace photography. Digital camera shutter speeds ended up too slow to seize a bullet flying at 2,800 feet for each second, but his stroboscopic flashes — a precursor to modern-day strobe lights — made bursts of mild so limited that a nicely-timed photograph, taken in an usually darkish room, produced it surface as if time experienced stood nonetheless. The outcomes were mesmerizing and, generally, messy.

“We utilized to joke that that it took a third of a microsecond (1-millionth of a second) to consider the image — and all morning to clean up up,” recalled his previous pupil and teaching assistant, J. Kim Vandiver, on a video contact from Massachusetts.

The 1964 impression has turn into 1 of the 20th century’s best-recognized images. Credit rating: Harold Edgerton/MIT courtesy Palm Push

Even though early digicam operators experienced experimented with pyrotechnic “flash powders” that mixed metallic fuels and oxidizing brokers to make a quick, brilliant chemical reaction, Nebraska-born Edgerton designed a flash that was considerably shorter and much easier to regulate. His breakthrough was far more a subject of physics than chemistry: Right after he arrived at MIT in the 1920s, he developed a flashtube loaded with xenon fuel that, when subjected to significant voltage, would induce electrical power to soar involving two electrodes for a fraction of a 2nd.

But, it was his 1960s bullet shots that proved some of this most memorable. In accordance to Vandiver, who still is effective at MIT as a mechanical engineering professor, the problem wasn’t generating a flash but placing the digicam off at just the correct time. Human reactions were too gradual to choose the photograph manually, so Edgerton used the sound of the bullet alone as a trigger.

“There would be a microphone out of the photograph, just down under,” Vandiver explained. “So, when the shock wave from the bullet hit the microphone, the microphone tripped the flash and then you would close the (shutter later on).”

Producing of an icon

A different of Edgerton’s famous photos, taken in 1957, displays the crown-like splash produced by milk droplets. Credit history: Harold Edgerton/MIT courtesy Palm Press

There was a different variable at enjoy: Edgerton’s inventive eye. The compositional beauty of his images observed them republished in newspapers and publications around the environment, and above 100 of his shots are held by the Smithsonian American Artwork Museum nowadays. Yet Edgerton turned down the added title.

“Don’t make me out to be an artist,” he has been quoted as stating. “I am an engineer. I am following the info, only the information.”

“We nevertheless teach the system, and students nonetheless consider of bizarre things to choose shots of,” he mentioned, recalling modern pictures of coloured chalk and lipstick torn apart by bullets. “Apples are tedious now.”