‘Hip-Hop Is About People’: Tracing Rap’s Rise Through Photography | News

“Hip-hop is about people,” says the journalist and director Sacha Jenkins, who has dedicated much of his life to documenting the art form. Jenkins, along with co-curator Sally Berman, last week opened the landmark show “Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious” at the Swedish photography museum Fotografiska’s Park Avenue outpost. As you first step into the exhibition, which runs in New York through May 21 before traveling to Stockholm and Berlin, you enter two rooms that feature striking photographs of people who saw hip-hop’s birth. Only a few of them have any significant name recognition, representative of a time when “hip-hop wasn’t conscious of itself,” Jenkins says.

These images solidify that hip-hop was a direct creative extension of its first home in the Bronx, a far cry from the glitzier stylings to which many modern fans may be accustomed. A 1983 photo by Martha Cooper shows a crew of kids carrying a piece of cardboard that they’ll use to breakdance, a shot that remarkably seems to mirror the Beatles’ Abbey Road cover art. It transports you to another time, a reminder that what has grown into one of the United States’ largest cultural exports was once just part of a small community’s lifestyle.

Launched in part to celebrate hip-hop’s 50th anniversary, the exhibition documents the origins and proliferation of this iconic culture in over 200 photographs and across two floors. “It’s a lot to squeeze in,” Berman says. The curators tactfully parallel hip-hop’s historical timeline, from its beginnings in 1972 all the way to 2022, with its regional expansion from the Bronx and its surrounding boroughs to other eventual hubs in the West and South. Snapshots of a street-based subculture organically flow into glossy images of the figurehead DJs and MCs that helped grow its name. “There’s a photograph of the Juice Crew, which is Marley Marl, Kool G Rap, MC Shan, Biz Markie, Big Daddy Kane, and Craig G,” Jenkins explains. “They’re in front of a private plane for the Marley Marl In Control Volume 2 album. When that was shot, hip-hop was slowly starting to come into its own.”

Documents from the early ’80s show legendary hip-hop statesmen in times when they were either already developing a live audience or on the verge of becoming recognized. There are images of rappers like KRS-One and MC Shan before their infamous 30-year beef, and before either had fully cemented their legacy. There are also captivating early photos of MC Sha-Rock, the “mother of the mic” whom Jenkins credits as being a “pioneer and very important person to the development of MCing.”

Just beyond this exploration of hip-hop’s initial New York boom is a wall highlighting some of the earliest commissioned photo portraits of MCs, dating back to the late ’80s. Particularly potent is a majestic black-and-white depiction of Queen Latifah shot in 1990 for the now-defunct British magazine Sky by prominent photographer Jesse Frohman. She wears sculptural fine jewelry and poses her right hand upright, seemingly blocking out naysayers. Here, hip-hop artists are no longer just a group of kids and young adults expressing themselves but pillars of music itself.

By the late ’80s and early ’90s, hip-hop was becoming a force in the West Coast scene. An eye-catching 1992 portrait by Shawn Mortensen shows Snoop Dogg, dripping in a Georgetown bulldog ensemble, pointing a gun at the lens. Before an all-black low rider, he kneels beside a large rottweiler. Rather than captured in the moment and on the fly, the imagery became more intentional and composed as the genre flourished in California, evidence of noticeably bigger shoot budgets. Part of what allowed hip-hop to grow in this era were the fiscal opportunities, supported in part by the emergence of prominent rap-led labels like Death Row Records.

“As time passes, the jewelry becomes more elaborate, the accouterments are more fancy,” Jenkins explains. “That is indicative of the connection between the power of language and culture with the power of marketing, sales, and manufacturing.” However, the transition from “the streets to corporate America,” Jenkins says, was not swift or concrete. Images strewn throughout exemplify the murkiness of the crossover. In Mike Miller’s photo of William LaShawn Calhoun Jr., otherwise known by his rap name WC, he stares boldly into the camera with a dirtied-up white T-shirt and a Los Angeles Kings beanie. A rugged crew of people stands behind him. While pursuing a music career, WC maintained a roofing business as a side hustle. Jenkins says he was most likely lensed as he was coming from a job.

Moving to the second floor, you venture back to the East Coast in an exploration of the genre’s mid-’90s to early aughts “golden era.” Naturally, there’s a Wu-Tang wall. During a guided tour a day before the show opened, Jenkins and Berman reflected on warm memories of past journalistic endeavors that the images spurred. Two grimy Ol’ Dirty Bastard photos reminded Jenkins of when he interviewed ODB at a rehab facility in L.A. He had offended the rapper when he told him he’d already spoken to his mother, so he bought him an Al Green box set to get back in his good graces. Berman recalled purchasing Ghostface Killa a Versace robe, per his request, so that he’d allow her to photograph him in his aunt’s Staten Island home. While that particular photo didn’t make the walls of this exhibit, she hopes the feelings she tried to instill as a photo editor for XXL and Respect are alive on these walls. “I hope people take away some joy,” Berman says. “I want people to have fun seeing this exhibit and walk away inspired by all the inspiration to make these images, by all the inspiration to make the music.”

This joy carries triumphantly into the red-walled next rooms, which cover hip-hop’s roots in the South. The rapper Future, photographed in 2016 by Theo Wenner, greets you with his arms outstretched next to a Lamborghini parked before an Atlanta Waffle House. The genre’s Southern movement began in the early to mid-’90s, yet its dominance landed later in the 2000s and 2010s. Jenkins retorted that the “Black Ellis Island was South Carolina,” a region that gave rise to jazz and the blues, genres that ultimately grew into the hip-hop that was born in the Northeast. One regal portrait depicts Ludacris smoking cigars with Scarface, the strongest MC from the legendary Houston group Geto Boys. It keenly represents a true bonding of the generations.

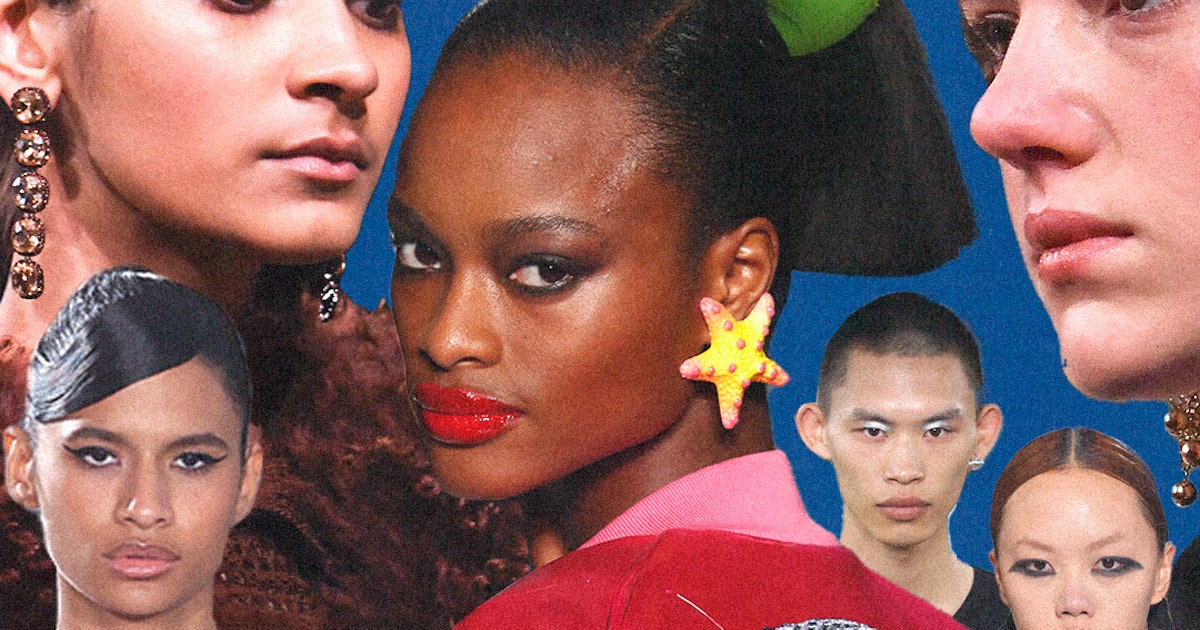

So what of the current generation of rappers and MCs? They’re here, too. We see everyone from Cardi B to Kendrick Lamar to Juice Wrld to Mac Miller grace the walls, primarily represented in high-resolution magazine portraits. Their inclusion acts as a poignant reflection on the journey of hip-hop itself: a rainbow of singular personalities, ruling pop culture through one of the world’s greatest art forms, yet grown from humble local beginnings. Jenkins breaks down the exhibit’s story structure as if it were an Aristotelian plot arc. “The beginning is hip-hop not really knowing who hip-hop was,” he explains. “By the end, hip-hop fully understands her power, her abilities, her influence, and her place in the world.”

Throughout the exhibit, there are plenty of hip-hop artifacts including flyers advertising an event in the Bronx written in pen on a flashcard, eight-track tape recordings of some of the earliest releases from the genre, and an original printing of the first journalistic reportage of hip-hop in the Village Voice. Jenkins’s favorite among them is a red Mobb Deep jersey from the “Shook Ones, Pt. II” video with “Hennessy” misspelled on the back to avoid lawsuits. Preservation is essential to a genre that has often had its impact discounted. “Hip-hop is a timestamp,” Jenkins says. “It helps people understand where we are in history. There’s a lot of hip-hop soldiers. We’re all in the war together.”