‘God told me I should take more LSD’: Sari Soininen on her acid-induced photographs | Photography

“The sky started to change slowly,” writes Sari Soininen in her photobook Transcendent Country of the Mind. “I could see and sense his rage from the movement of the clouds, which started to get darker and darker. It felt like I had stepped into the Book of Revelation.”

The Finnish photographer had in fact fallen headlong into the hallucinatory intensity of an LSD trip and was undergoing the first of several acid-induced experiences that would culminate in a prolonged bout of psychosis. What had started out as a “heavenly experience”, when Soininen first tried the drug aged 24, soon turned much darker and stranger as she became convinced that God was communicating directly with her.

“He told me I should take more LSD in order to become connected to this revealed world where everything was connected,” she tells me, matter-of-factly. “So I took it regularly for about three months. At one point I was convinced I was going to give birth to a new baby Jesus. It turned really dark when the devil appeared.”

On one level, Soininen’s first-hand testimony of her LSD-induced bout of psychosis, which lasted around four months, is the most viscerally powerful element in her photobook. It provides a nightmarish counterpoint to the more subtly disorienting images she has made in an attempt to evoke the altered reality she experienced while under the influence of the hallucinogenic.

“I’m not trying to evoke what I went through, because that would be impossible,” she elaborates. “It’s more about what has stayed with me from that time. With photography I can transform reality, but I can also question the nature of reality itself so there’s a philosophical aspect to it. I have always been sceptical about what is the true nature of reality. I still am, probably more so because of what I experienced on LSD.”

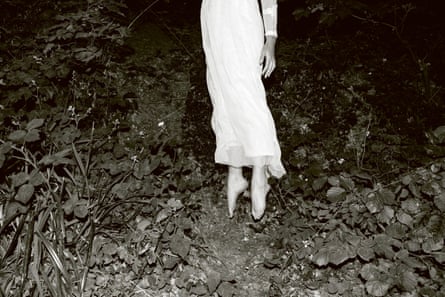

In Soininen’s photographs, the world is rendered otherwordly and everyday reality seems heightened and elementally mysterious. The branches of spreading trees seem electrically charged with light; a flock of pigeons hover in the air as if suspended; hedgerow flowers glow with an infra-red intensity. Soininen eschews post-production trickery, instead using colour gels when shooting. Blessedly she does not attempt to describe the psychedelic experience in all its sensory overload. Instead, her images are freighted with subtle clues that suggest the ways in which the drug can alter people’s perceptions as well as erode their logic and rationality.

Nature is both a celestial presence and a subliminally threatening one: trees resemble human torsos; cats appear demonic; a pothole is a portal into darkness. Here and there, humans loom into view, their faces smooth and pale and featureless or obscured by clouds of smoke. She also captures moments of luminous natural beauty: sunlight filtering though slats in a wooden fence; sinuous branches reflected in water.

I put it to her that her post-acid vision seems animistic, shot through with the transcendent wonder of nature. “Well, when I first tried LSD,” she says, “I was in the countryside and the sense that everything is connected to nature was one of the most powerful feelings I experienced.” Did the biblical, almost apocalyptic, nature of her imaginings stem from a religious upbringing? “No, not at all, but I’ve always been interested in paganism and Christianity as ways of explaining the supernatural. I think those ideas are in our culture so I absorbed them on some level.”

Now 31, Soininen studied photography in her early 20s in Finland but, like everything else in her life, it stopped making sense to her during her years of acid experimentation. When she speaks about that time, she is philosophical about her rapid descent into psychosis, and remarkably matter-of-fact about the wild visions that consumed her like a kind of mania.

When she re-read her journal notes from that time, she realised she had become obsessed by the idea that she could definitively prove the existence of God. “I wasn’t hearing voices at that point,” she elaborates, “but I had this deep intuitive feeling that I had to do certain small things to make the revelation happen. People around me didn’t know what was going on. I remember going back to my parent’s house and slamming the Bible on the table and my dad going, ‘What the fuck are you doing?’ It was an intense time.”

That is putting it mildly. In the extraordinary prose passage she has written for Transcendent Country of the Mind, she relates a manic car journey she undertook with her boyfriend, both of them sharing an LSD-induced vision that they were en route to “a new world” – perhaps the transcendent country of the book’s title. It culminates in a fractured account of the car crash that occurred when she closed her eyes at the wheel as they entered their imagined destination, while he sat blindfolded beside her. Miraculously they escaped serious injury. They were arrested as they walked along the roadside soon afterwards. Later, when the police gained entry to her apartment, they found it empty. “I had thrown away everything I owned,” she writes. “I had thrown myself away and been born again.”

Having experienced heaven and hell, she is lucky to have come through with her faculties intact, I say. “Yes, but it has profoundly changed me – and the way I look at the world,” she replies. How did she finally emerge from that wild, destabilising time? “Well, my last trip was pure madness. But three weeks afterwards I started to get back to reality. It began when I walked into a hospital and told the nurse that she looked like the devil. They could see I was in a bad way and they gave me medication for a week and all the madness started to melt away.”

Having rebuilt her life, Soininen returned to photography, completing an MA at UWE Bristol last year. She is now based in Helsinki. Transcendent Country of the Mind began life as her postgraduate project, taking shape almost by accident. “Initially, I was interested in doing a project on Finnish paganism” she says, “But, looking back, I think that was because I didn’t want to say out loud that I’d experienced psychosis from talking too much LSD. For a time, I didn’t really know what I was doing other than that I was walking around photographing these seemingly unconnected things that were somehow important to me. I came to understand the project by doing it.”

On some deeper level, has photography – and, in particular, the making of the book – proved therapeutic? “I think so, yes. It has been healing, but also more than that. To be honest, the world can sometimes seem banal to me now, but with photography I can see it in a different way. When I was making Transcendent Country of the Mind, it sometimes felt like I was somehow building an imaginative world, this other reality, inside the world that we live in.”

-

Transcendent Country of the Mind by Sari Soininen is out now, published by the Eriskay Connection, priced £30