Eddie Vedder Is Still Learning to Live With Loss

A solo effort from a member of a long-running rock band can be an iffy proposition, the music in danger of being scuttled by either self-indulgence or transparent bids for greater individual stardom (or both). Eddie Vedder, the lead singer of Pearl Jam, sidestepped those problems on his 2011 solo album, the quaintly charming and musically humble “Ukulele Songs.” His new one, “Earthling,” out Feb. 11, is an altogether different, more ambitious effort. The album features guest appearances by Stevie Wonder, Elton John and Ringo Starr and was produced by Andrew Watt, a hitmaker known for his work with such contemporary pop musicians as Justin Bieber, Post Malone and Miley Cyrus. As such, it’s likely that the album will contain some surprises for those listeners who mainly know the singer as an avatar of ’90s-era rock-star angst, as well as for the army of die-hards who have continued to ride Pearl Jam’s various waves. “When the songs are coming out,” says Vedder, who is 57, “it’s usually because they’re songs that I would like to hear myself. It’s like I need a paint color that I’ve never seen, so I mix it myself. Hopefully people trust us to come up with new paint colors that they care about too.”

You made your new album with a young producer who has had pop success. You’ve also got these older legends on it. The fact that you reached both forward and backward generationally for your collaborators made me wonder: Have you been thinking about how to attract listeners beyond Pearl Jam fans? And I know the humble answer would be, “I’m happy if anybody listens,” but I’d rather hear the honest answer than the humble one. I wouldn’t want anything to be not honest. That’s what could be scary about this interview, and I like that. The honest answer is that I should think about that stuff, but I don’t. It’s funny because all the people that you mentioned, working with them just kind of happened. Andrew was working with Elton to finish his record, and I’d been called in to scribble out some lyrics. Stevie was also working with Andrew on that record, so then we had a relationship. Stevie, it was incredible to watch him work. At one point it was almost like he disappeared as a person and became a musical entity, a vessel. I get chills thinking about it.

But to stick closer to the initial question: Who do you think your audience is now? And what might those people be getting out of your new music? I don’t know. People tell me powerful stories about what the music means to them, so, in that way, I know what they get out of it. When people tell me that stuff, I don’t feel like I should get credit. They’ll say that a song helped them, but, ultimately, I’m like: “You did it.” Really all I can do is hope that other people appreciate the music that I like. I’ve had conversations with Bono back in the day. He was suggesting that we needed to work harder and that you didn’t want rock ’n’ roll to become a niche. He said that when U2 makes a record, it’s like they’ve got a racehorse and they don’t just want the horse in the race, they want to win the race. I said we race the horse and then we let the horse run free. I wasn’t trying to be clever. That was the truth. He was frustrated with me. But the dream was to be in a group that toured and recorded, and we were OK with things being scaled down if that allowed the dream to survive.

Eddie Vedder performing at Madison Square Garden in 2008.

Kevin Mazur/ WireImage/Getty Images

Just going back to what Bono said: Was he overlooking the fact that time moves on and the race becomes unwinnable? Doesn’t rock’s place in the culture affect how you understand the parameters of your job? One thing I’ll say: I would go see Dead Moon, these three people with the candle on the drum set and the ritual and the sweat and the love — those were some of the most glorious shows of my life. As good as the Who in 1980 at the San Diego Sports Arena; as good as Fugazi shows where everyone paid $5 and it was at a V.F.W. hall. There’s nothing in any other type of music that can ever eclipse that. So I guess I don’t think about what you’re asking. At the risk of sounding whatever, we haven’t had an issue selling tickets over the years. If there’s been ebbs and flows in the amount of people that care, we’ve had enough people that cared and continued to care that we haven’t noticed. I don’t know if that’s been for better or worse. At least we’re not chasing anything.

I have a question about not chasing things: When you got started in music, the idea of not selling out was central. Now the concept has basically disappeared. This is good news! This means that the fragrance that I’m about to put out won’t be looked down upon!

“Smell Out”! But along those same lines, there also used to be so much more ambivalence about fame. How did we get from there to here? As far as fame, when we were getting successful, it was like being on a freight train. You’re in the engine room; there are no windows; you feel the velocity but don’t know where the train is going; there might be limited communication with whoever is in the conductor’s seat. When you realize that’s happening, you try to take over the train. We thought, We’ve got to slow down or change direction because there might be a bridge that’s blown out and it’ll all go away. But to circle back to selling out: You could be a band that was concerned about ticket prices, concerned about T-shirt prices, concerned about ticket surcharge prices — you could do all that and then, cut to 10 or five years later, and music was not something that people had to pay for. Is that part of the evolution? People said, If nobody is going to pay for the music, then we’re going to have to figure something else out. You had to find other ways to maintain.

Pearl Jam in 1992.

Niels Van Iperen/Getty Images

Do you think any ripples from that Gen X, alt-culture explosion extended to the present? You know, I used to work in San Diego loading gear at a club. I’d end up being at shows that I wouldn’t have chosen to go to — bands that monopolized late-’80s MTV. The metal bands that — I’m trying to be nice — I despised. “Girls, Girls, Girls” and Mötley Crüe: [expletive] you. I hated it. I hated how it made the fellas look. I hated how it made the women look. It felt so vacuous. Guns N’ Roses came out and, thank God, at least had some teeth. But I’m circling back to say that one thing that I appreciated was that in Seattle and the alternative crowd, the girls could wear their combat boots and sweaters, and their hair looked like Cat Power’s and not Heather Locklear’s — nothing against her. They weren’t selling themselves short. They could have an opinion and be respected. I think that’s a change that lasted. It sounds so trite, but before then it was bustiers. The only person who wore a bustier in the ’90s that I could appreciate was Perry Farrell.

You’re relatively rare among male singers in big rock bands in that you write sometimes from the perspective of women, including on the new album’s “Fallout Today.” You’ve also been outspoken for a long time about abortion rights, which is also, I think, rare for men in your position. How did that sympathy develop? Without getting into specifics, my thinking about abortion germinated from personal experience. The issue has only grown in importance for me. The real issue is not allowing women to have control of their own bodies and their own futures. If it was a men’s issue, it wouldn’t be an issue. I’ve always felt that as males maybe we shouldn’t be part of the discussion. I would gladly surrender my place in it if every other man did too. It’s frustrating because we’re rehashing issues that seemingly had been dealt with fairly responsibly. It reminds me of “Bob Roberts”: “The times they are a-changing back.” The fact that these rights are still in jeopardy — it feels like we’re trying to cure polio again.

It remains the case — unless I’m making unfair assumptions — that there are probably plenty of people in the audience at your shows whose politics are more conservative than your own. Is that ever perplexing? A singer in a rock ’n’ roll band is not going to be able to reshape all the things that he’d like to. You can maybe suggest ideas; maybe some people sing along to something, and they don’t know what it’s about until one day it clicks. I’ve had it happen where I didn’t understand a Who lyric until I was in my late 30s and I’d been singing it since I was 14: “How Many Friends?” But who is the audience, or how can I reach them? I don’t have the bandwidth for it.

Is it possible that you’re being a little disingenuous? To pick an obvious example, what is “Not for You” if it isn’t a song about the relationship between artist and audience? Is your thinking here different than it used to be? I’m sure there’s been an evolution in everything we do. It used to be youth against establishment and chaining yourself to old-growth trees and seeing how that played out. Then it evolves to how do we actually get things done? Because it seemed like rattling the cages was simply that, and rattling the cages is probably where some of those naïve lyrics came from. But at some point it was like, What do we want to achieve? We started trying to meet with our adversaries to see what could be done: funding the preservation of rainforests to offset carbon emissions. We had the Ticketmaster thing — didn’t work. They made it go away. That was a learning experience. It bruised our muscle of idealism. We were young and naïve and thought you could change things. But just taking on the man and being agitators, it might not be the way.

Just quickly, since we touched on lyrics: When you were recording “Yellow Ledbetter,” didn’t you ever listen back and think you needed to tighten up the enunciation screws? [Laughs.] No. That would assume I ever listened back. I didn’t. Have I listened back to every other song since? Maybe.

Kurt Cobain is someone who comes up as an influence on your and Pearl Jam’s evolution. But I’ve never heard you explain — in a concrete way — how that influence manifested itself. Can you? The things that I remember sound inconsequential. I remember hearing through the rumor mill that Nirvana had got a big check, and that seemed exciting. We were excited for them — and wondering if we’d get a big check. I also remember going over to Krist Novoselic’s. Krist had two jukeboxes: One was LPs, one was 45s; he had two pinball machines. I remember thinking that if Krist did that, then we could and it wouldn’t seem bourgeois. Outside of that, I remember it was cool that Novoselic asked me, when the record was coming out, it might have been the second record — oh, [expletive]. Now I know why I never tell this story. Here’s the problem: I’m about to mention the Beatles and the Stones. He was saying that he’d read back in the day — I don’t know if he was right — that the Stones and the Beatles used to see when each other’s records were coming out so they could put them out at different times. I thought that was one of the biggest compliments. Not remotely because we were like the Beatles and Stones but because he was saying, Hey, we could work together on this.

Is it telling that I asked you about Kurt Cobain’s influence and you told me Krist Novoselic anecdotes? I didn’t know Kurt that well. We had a few hangs. I’m grateful for those or those phone messages or being in the same room every once in a while, but it would be offensive to claim that I knew him more than I did.

Was his influence maybe more attitudinal from afar? Oh, that’s a good point. That could be. Explain that a little more?

His attitude toward celebrity and the music business was full of skepticism and irony and sarcasm, which I imagine would have been influential among other Seattle musicians, and also maybe not you and your bandmates’ natural inclination. So the question is whether observing his attitude about rock stardom and the expectations and machinery around it made you rethink your own attitudes? To hit it as close as I can: That was naturally how we felt. I know it’s how I felt. But I think that his attitude made it OK to feel that way because he was the guy in the biggest spotlight. If he would’ve totally embraced all that stuff, it might have made me think, like, you better embrace this [expletive], too. You couldn’t argue that he wasn’t the figurehead of that whole thing. That’s probably one of the things that bummed him out the most. That was a good question. I hadn’t thought about the attitudinal side.

Pearl Jam performing in Amsterdam in 1992.

Niels Van Iperen/Getty Images

You guys in Pearl Jam have been working together for more than 30 years, which is unusual for any group of people, let alone a band. What do you know about compromise? You could say compromise, you could also say acceptance. I feel that in some ways artistically it’s been better in the last 10 years than ever. In the old days — and I’ll speak for myself — there was more being selfish or insecure. Do I have enough songs on this record? What’s my input? We’ve matured enough to accept each other the way we are and also accept the way that we’ve grown. It’s less territorial. Everyone feels heard.

Not to ask the jerky question, but what do you say to the idea that it’s good that you guys are having a better time making the records but maybe the records were better when it was a struggle? Our job is not to make records that people like. Our job is to make the music that makes us feel proud. I’ve been pondering your questions: Is there something I’m missing here? Am I supposed to be thinking about what other people are thinking? Because with songwriting it’s almost like you can’t think about it in order to let it happen. Getting to some authenticity or relaying some experience — it’s about getting out of the way.

There is one song in particular on the new album that I’m hoping you can talk about: “Brother the Cloud.” To my ears it sounds like it’s about trying to understand the suicide of a friend. I have my own hunch, but can you tell me what inspired it? I’d rather leave it interpretive. The general thing I can say is that some people leave this planet, and it could be by accident, design, tragedy or all of the above.

The line that I keep thinking about is “Put your arms around my brother, my friend, say for me, [expletive] you.” In the larger context of the song it sounds like you’re getting at the anger that can come alongside the sadness of a suicide. Is that off the mark? Well, it’s frustrating when you are deeply saddened by a loss, but it’s out of balance with the anger that you feel.

I lost my best friend to suicide, and I’ll say that the link between sadness and anger in that song is very recognizable. Can I ask you about that?

Oh, gosh. I don’t know if I have anything to say. I know it’s personal. But just so I have another perspective.

Yeah, OK. How is your level of forgiveness? Has it stopped growing? Do you feel like it will keep growing? I think the mature thing is to understand that maybe it wasn’t completely his choice. How have you felt about the forgiveness?

I think it’s about finding a way to accept conflicting feelings. Now I have it to where 90 percent of the time I feel gratitude for having had that person in my life at all. The other 10 percent of the time I think, Why did you do that, you idiot? Ninety percent is very good. I wish I could get to that. And then how much do you feel the frustration of, OK, we were that close, and you didn’t come to me?

I’m sorry, it makes me emotional to talk about. I don’t want to hijack this interview. You’re relating to something. It’s valid.

Of course you go down the rabbit hole of: Why didn’t he call that day? What if I’d called that day? But that’ll drive you crazy. It’s not fair to beat yourself up about that. Is that what you’ve been doing? Maybe that’s why the song was there waiting to get out. The music goes where it goes.

I don’t want to get too heavy, but the amount of loss among your direct peers is striking. Have you ever been able to make sense of why them and not you? You’d have thought I would have had tons of people to talk with about it. I remember at one point being down because of life-shattering events happening in close proximity to one another — feeling kind of fetal position. The worst was feeling that I didn’t have anyone to talk to. I guess this is me putting myself on the other side of what you just talked about, it might help me come around to forgiveness or acceptance: I felt that I was there for so many people, that I was a bit of stability, and if they knew that I was having an issue they’d be like, If he can’t keep it together, we’re all [expletive]. But I didn’t want anyone to know. That was something I had to get over, and maybe not everyone is able to do that and get with close friends who have wisdom to impart — the simple thing of going to bed and waking up and trying again.

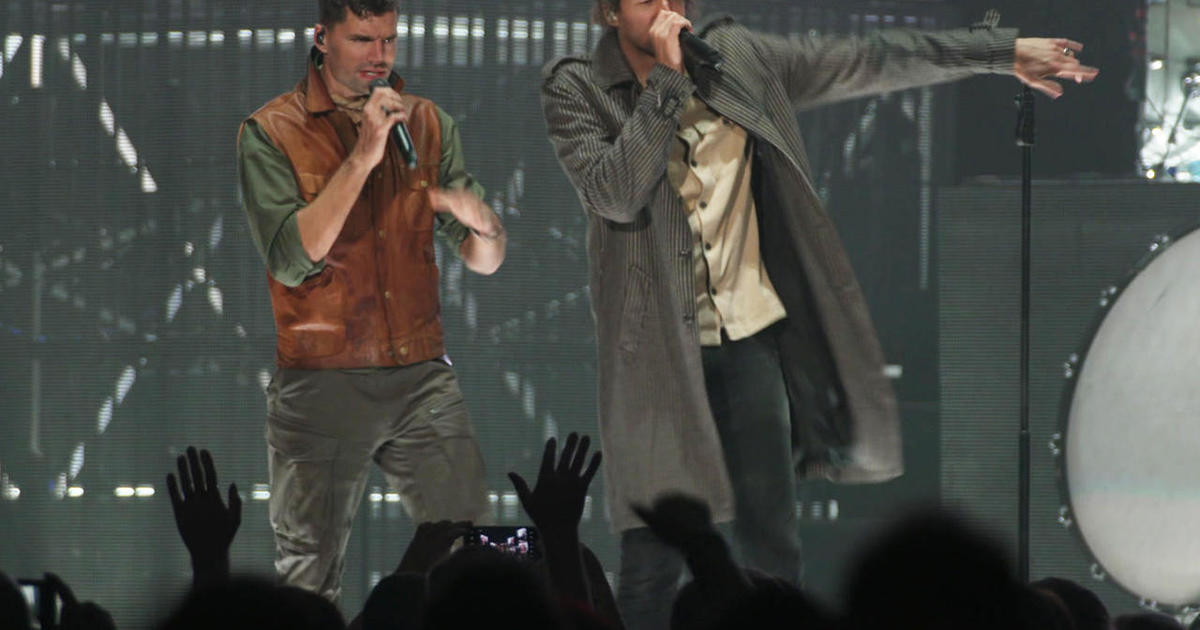

Vedder on stage in Johannesburg in 2018.

Kevin Mazur/Getty Images

Let’s move on to something brighter: Your biological father’s voice is on the album’s last song. What’s the story there? Yeah, the album is structured kind of like a concert: The special guests come out at the end. Stevie, then Elton, then we’ve got our “Mrs. Mills” song with Ringo. Then the last special guest was my father, whom I really didn’t get to know.

It’s a well-documented story. Yeah. The short version of this story is that it was through a baseball player on the Chicago Cubs. His name is Carmen Fanzone. He’s also a very accomplished trumpet player. I got to know him and go see him in Arizona during spring training or something and the keyboard player in this little four-piece combo is this guy, Danny Long. He said to Carmen that he thought he was friends with my dad. So two years later I see Danny again, and he brought a manila folder full of pictures of my dad that I had never seen. Two years after that he brought a CD with four or five of my dad’s songs. I was afraid to listen. Then I put it on, and it was great. He really could sing. I played them for Andrew, and we decided to turn it into a collage at the end of the record. It was a happy landing. I like those.

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (TALK). You can find a list of additional resources at SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations.

Opening illustration: Source photograph by Jon Kopaloff/WireImage/Getty Images

David Marchese is a staff writer for the magazine and the columnist for Talk. Recently he interviewed Brian Cox about the filthy rich, Dr. Becky about the ultimate goal of parenting and Tiffany Haddish about God’s sense of humor.