‘People arrived for work and got vaporised’: how Kikuji Kawada captured the trauma of Hiroshima | Photography

Kikuji Kawada was 25 when he frequented Hiroshima for the 1st time. It was July 1958 and he had been assigned by a Japanese news journal to support Ken Domon, a renowned photographer 14 yrs his senior. As Domon labored in and all around the Hiroshima Peace Park, Kawada uncovered himself drawn to the ruined shell of a after ornate, steel-framed setting up that experienced been poorly ruined, but in some way remained standing, when The us dropped the initial atomic bomb on the city at 8.15 am on 6 August 1945, obliterating all the things else inside of a mile radius.

“That’s when I identified them,” he would later recall, “the stains on the walls of the rooms beneath the dome.” The bomb had been dropped from pretty much specifically over the building, which was then known as the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Advertising Hall. By itself in the dank ruins, Kawada realised that the stained partitions held the only traces of some of the useless. “When the spot was ruined,” he instructed Aperture journal in 2015, “there had been about 30 persons (who) experienced arrived for operate and ended up vaporised. The spot experienced a awful atmosphere. Just on the lookout at it was frustrating.”

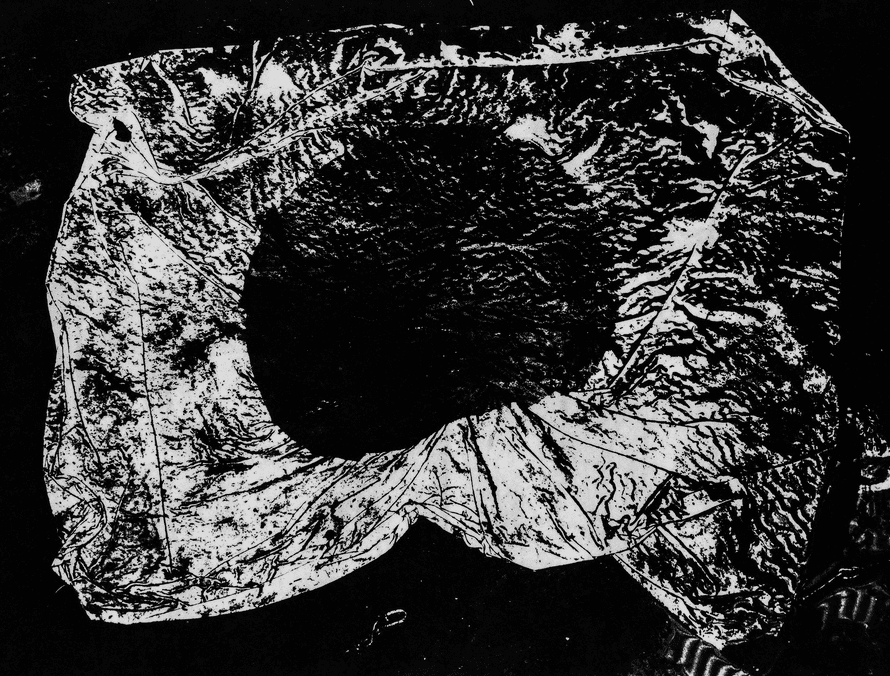

Haunted by what he experienced found, Kawada later on returned to Hiroshima with a massive structure 4×5 plate camera and, employing only the natural light-weight coming however the shattered dome overhead, commenced photographed the eerie styles on what is now regarded as the Genbaku (A-Bomb) Dome, a memorial to the victims of the bombing. The “stain” photos, as they have arrive to be identified, are the emotional and conceptual darkish coronary heart of Kawada’s guide, Chizu (The Map), which was first released in an edition of 500 in 1965. “It is,” says the British photographer Martin Parr, “the holy grail of Japanese photobooks.”

In the late 1990s, Parr, an avid photobook collector, managed to track down a rare initial imprint in a bookshop on the outskirts of Tokyo. “It value me £10,000” he tells me, “and it is now value about £25,000.” He describes it as “the ultimate example of the photobook as artwork item. It ticks each and every box: the photographs, the bold structure, the fantastic use of gatefolds, just the superb intricacy of it all.”

Designed by Kōhei Sugiura, the unique edition of The Map is an item of elaborate attractiveness and unsettling electricity. Printed in higher contrast black and white, it is a ebook you delve into, the double gatefolds opening out to reveal pictures that appear resonant with further indicating. Grainy pictures of day-to-day objects – Coca-Cola bottles embedded in the floor, a crumpled Fortunate Strike cigarette packet, a trampled Japanese flag – discuss of the disruptive impact of American imperialism on Japanese society. The trauma of the next entire world war resonates in photos of ruined buildings shot from down below at odd angles, brutalist concrete bunkers and ribbons of twisted scrap metallic that emerge, hardly identifiable, out of web pages of inky blackness. His photos of the stains are redolent of abstract paintings and evince a dark, unsettling aura that is as considerably away from common photojournalism as it is doable to go.

The Map took Kawada 5 a long time to comprehensive and amounts to a personal archeology of postwar Japan’s collective discomfort that is the two deeply resonant and wilfully elusive. For all that, as Joshua Chang, senior curator of photography at the New York Public Library, notes in his introduction to a new edition, the photographer later on “expressed a diploma of ambivalence about the book that turned his contacting card. He most well-liked in its place the two-quantity maquette that he experienced at first established, but later deserted, as his collaboration with Sugiura deepened.”

In 2001, the New York Community Library acquired that handmade maquette and the new Mack version of the book is a facsimile of the similar. It is a radically distinctive artefact: a two-volume book (with an accompanying volume of texts) that is twice as massive as the unique, with various tones and picture crops, and minus the gatefolds that were being so central to the wilfully disruptive narrative thrust of the initial edition. Instead, a succession of whole-bleed visuals unfold in the fashion of a much more regular photobook. That explained, the maquette version is wonderfully manufactured and emphatically Japanese, dating from an period of wild and irreverent invention in picture-making and design.

Owning co-started the Vivo collective in 1959, Kawada was aspect of a groundbreaking era of Japanese photographers that provided the likes of Eikoh Hosoe and Shomei Tomatsu, whose impact carried while to the Provoke era of the late 1960s.

“The most remarkable photobook publishing was accomplished in Japan in the 1960s and 70s,” claims Parr. “It speaks volumes about the vanity of the west that, up until the 1980s, the remarkable innovation of Japanese photographers and designers was all but overlooked. The Map is now typically regarded as the icon of Japanese photobooks of that period.”

For all but the most avid collector, Chizu (Maquette Version) is as close as we will get to the visceral, unsettling electricity of the first version. It is a beautiful item in by itself, but its visual mapping of history, trauma, memory and horror appears to be considerably less mysterious and multilayered than its intricately built predecessor. Whichever the variations, though, the dim epiphany that marked The Map’s conception resonates just as deeply in both of those occasions.

“It was an unspeakably powerful instant,” remembers Kawada in an interview that accompanies the recently published edition, “I felt like I experienced encountered this terrifying, unknown spot. I had the illusion that I could practically hear faint voices merged with the wind and crackling sounds coming out of the wall.” You can virtually feeling his unease as you flip the pages.