The first man to hunt wildlife with a camera, not a rifle | Photography

In 1909 two wildlife safari expeditions arrived by ship in Mombasa, Kenya, within days of each other. One party was enormous and led by the adventure-loving US president Teddy Roosevelt; the other consisted of just two men and was headed by Cherry Kearton, a young British bird photographer from Yorkshire.

Over several months on safari the trigger-happy president and his son Kermit killed 17 lions, 11 elephants, 20 rhino, nine giraffes, 19 zebra, more than 400 hippos, hyena and other large animals, as well as many thousands of birds and smaller animals. By contrast Kearton, the first man in the world to hunt with a camera and not a rifle, killed just one animal, in self-defence.

The two men came from different social worlds and had contrasting visions of the importance of wildlife. Roosevelt justified his massacres by saying he killed for science and education; Kearton was not against shooting “for the pot” but said he took pictures for the love of it. But when they met in the Kenyan bush, they struck up an unlikely friendship, with the president letting the photographer capture unique film of him setting out on one of his bloodbaths.

The footage was poor quality but it earned Kearton enough to set up with his brother Richard a London film studio that gave birth to the world’s first wildlife documentary films – now a staple of TV, and possibly the single most important medium today for people to appreciate nature.

Kearton’s work as a pioneer of nature photography will be celebrated later this month in a small exhibition that will show 37 of his “lost” pictures of lions, leopards, rhino and other wildlife discovered in an old desk last year by his great-granddaughter Evie Bulmer, as well as 30 minutes of cine-film that he shot in Africa and is now held by the British Film Institute.

Kearton called Roosevelt “a dear friend” but was appalled by his hunting. He wrote later: “[T]o help in the least degree to accomplish the extinction of anything beautiful and interesting is a crime against future generations … Unfortunately, this is a crime that we have all been complicit in committing.

“It is as a naturalist that I view the wanton slaughter of game with such abhorrence … I raise my voice with all its force against the wicked and wanton destruction of big game.”

Kearton was far ahead of his time, says Bulmer, popularising nature for the Victorians in the way that David Attenborough and others have done for modern audiences. “His fascination with recording the world’s wildlife through photography was unique in this period. It focuses on promoting Africa as the playground of the animal rather than the hunter,” she says.

Starting in the 1890s, he and his brother Richard acquired a cheap box camera and shot the first-ever pictures of birds’ nests with eggs and made the first recordings of birds in the wild. They progressed to massive “collodion” plateglass cameras, but without zoom lenses or rapid-speed shutters they had to devise ever more extraordinary dummy hides to get as close as possible to nervy wildlife.

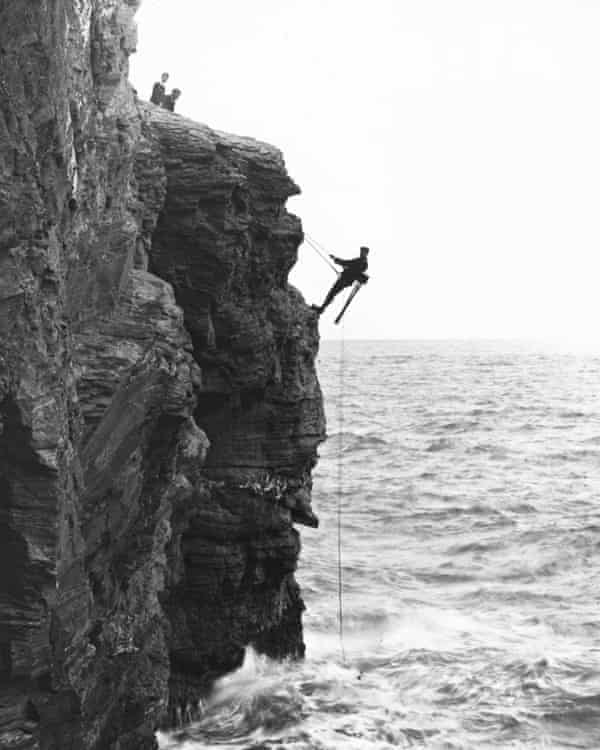

One solution was to have a taxidermist make a full-sized hollow ox, which they would plant in fields and then crawl inside with the camera lens poking through a hole in its head. Another was a mobile heap of hay and grass that Richard used to hide in; there was a stuffed sheep with a pneumatic camera, artificial rocks, false tree trunks and masks. Together the brothers took enormous risks, abseiling off high sea cliffs, standing in rivers for hours, waiting all night, and climbing the highest trees to film birds in their nests.

Attenborough acknowledges the brothers’ influence. In a letter to Bulmer, he said he was “at the age of eight taken to see a film lecture presented by Cherry Kearton. [It] captured my childish imagination and made me dream of travelling to far-off places to film wild animals.”

According to the Keartons’ biographer John Bevis, “the world in which Cherry lived was preoccupied with capturing, killing and stuffing animals for display or to complete a collection. Cherry was unique in his desire to photograph animals undisturbed in their natural habitats. He was less zoologist than nature lover, less educator than crusader. His intention was not to produce film made by scientists for scientists and seen by few but scientists … but an alternative to the ubiquitous big game and hunting features.”

Cherry Kearton went on to be a war photographer, and died in 1940. “If through my books, still pictures and films the public can gain a wider knowledge of the animal creation, and consequently a deeper sympathy, I shall be satisfied,” he wrote.

-

The exhibition With Nature and a Camera is at the Royal Geographical Society, London, from 14 to 20 December.

-

The Keartons: Inventing Nature Photography, by John Bevis, is published by Uniform Books.